July 12, 2021

These (inflationary) effects have been larger than we expected, and they may turn out to be more persistent than we expected, but the incoming data are very much consistent with the view that these are factors that will wane over time, and that inflation will move down toward our goals, and we’ll be monitoring that very carefully.

— Fed Chairman Jerome Powell, Congressional Testimony, June 22, 2021

It is easy to take for granted how far our country has come over the past six months. In early January, the number of new Covid cases was running near 300,000 per day, with about 4,400 Covid-related deaths each day. As of the latest report, the number of new Covid infections is down to about 12,000 per day, and the number of deaths is about 300. This in just six months! It is a testament to the extraordinary accomplishment of scientists who developed vaccinations in record time and with exceptional efficacy. Surely this work deserves a Nobel prize in medicine, and perhaps a Peace prize as well.

After 15 months, many aspects of life are slowly returning to normal. It is possible to see family, attend weddings and graduations, and hug your children and grandparents. It is possible to have a nice meal out, and that surely beats lukewarm food delivered and dropped off at your front porch. It is possible to travel, at least domestically, and each of these fairly simple accomplishments was not possible six months ago. (If you are short of time or patience, consider reading the bold only.)

In something out of science fiction, global economies were shuttered, almost as if a huge switch was thrown, and the gigantic global engine ground to a halt. Imagine the sound that shut-off would have made, and then silence. Now we are trying to throw the switch to turn everything back on, and the giant machine has started sputtering and spinning. Why are we surprised that there are problems along the way?

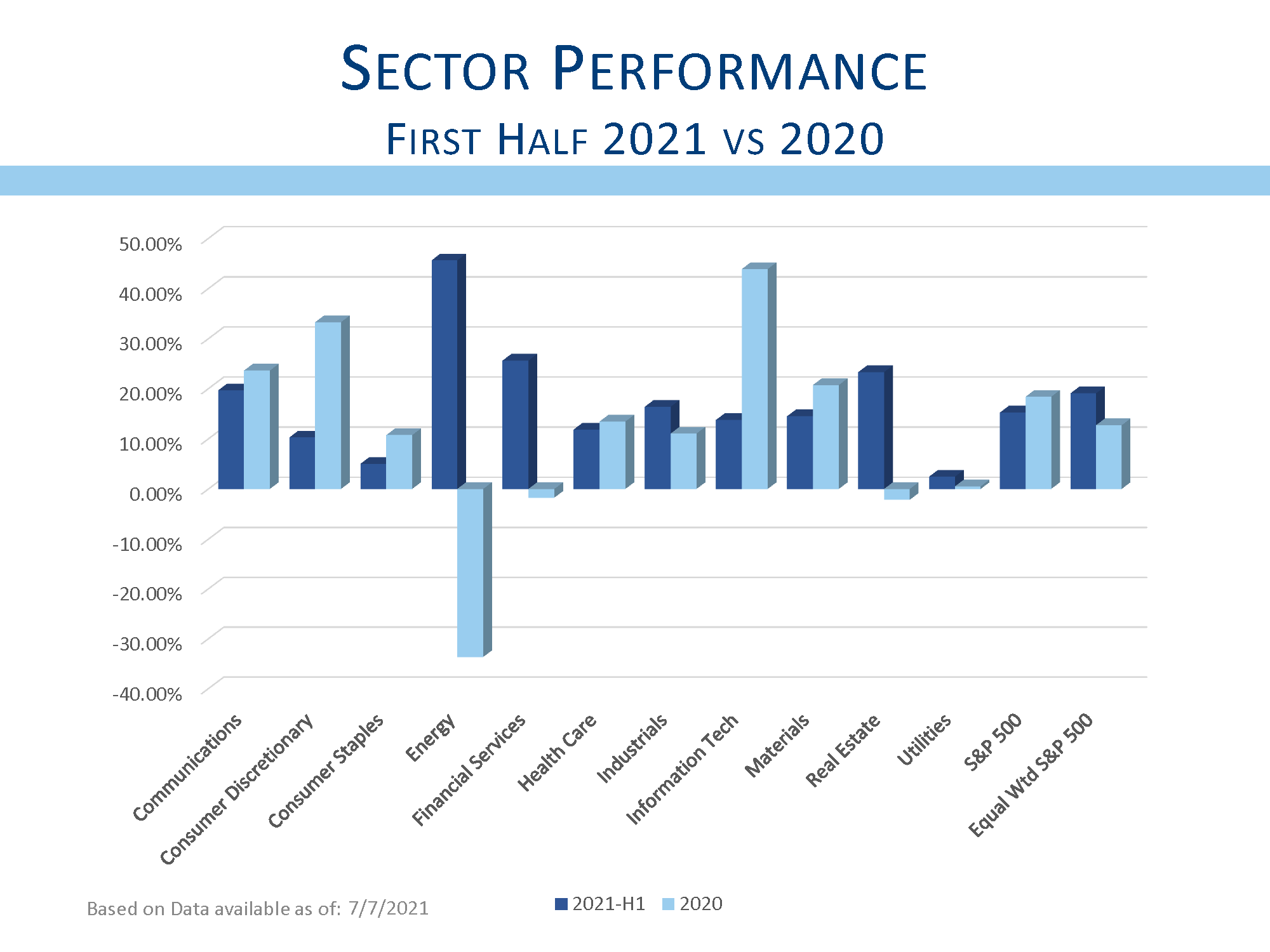

We are seeing shortages of parts, semiconductors, commodities, and workers. This has created inflationary pressures that we will come back to. It has also changed the investment environment. Those sectors that performed the best in 2020 are now lagging, and the sectors that lagged the most last year are now leading. Many of the companies that provided software to enable us to successfully work from home are now viewed as far too expensive. This is partially due to the fact that some companies are requiring employees return to the office, so we may have passed the peak opportunity to work from home. Additionally, many of the pandemic “heroes” reached valuations that are very difficult to support, and some prices have started to return towards earth.

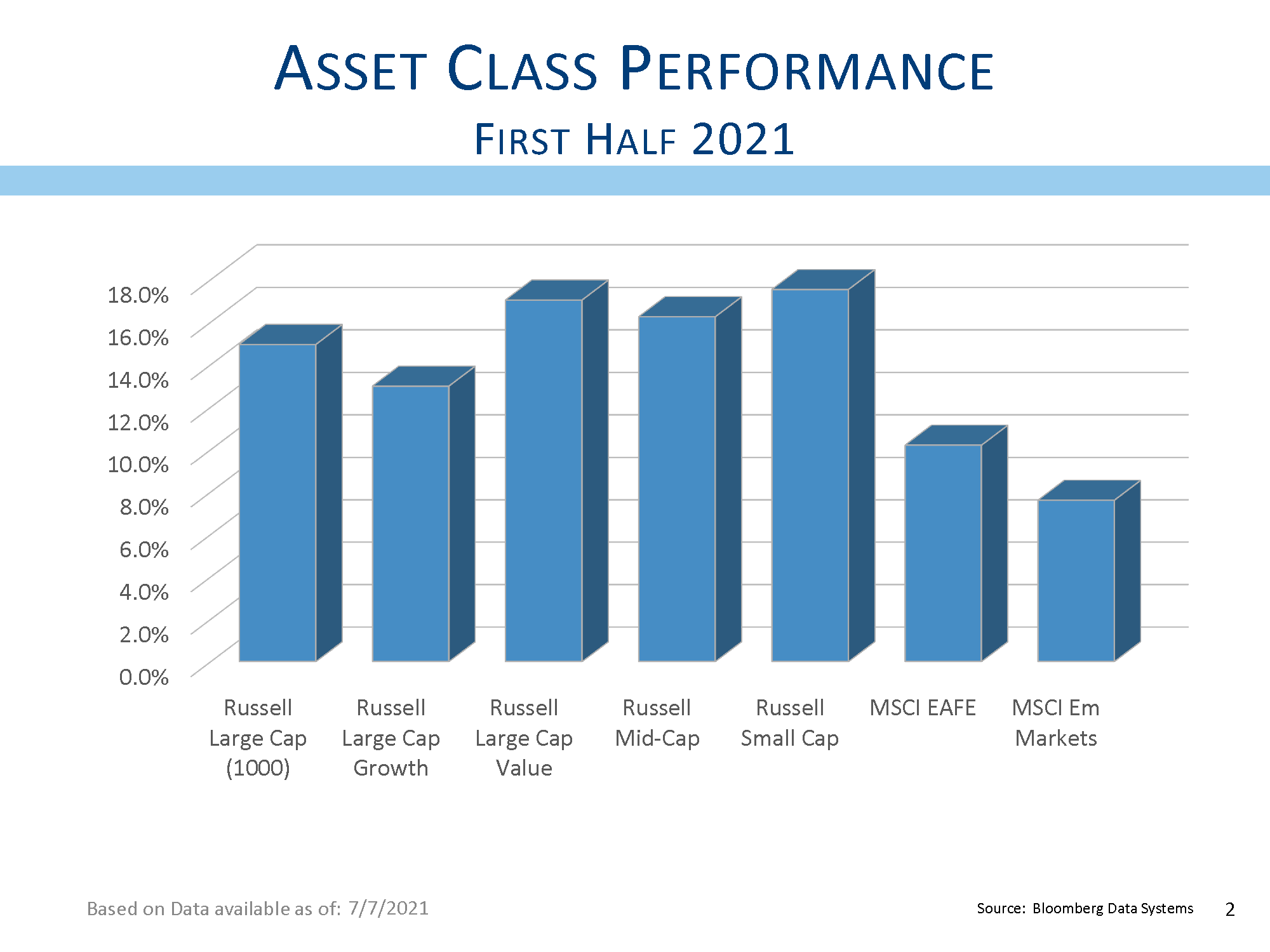

Work-from-home stocks have been replaced with economic recovery stocks, and energy stocks have been some of the best performers this year. In a strong economic recovery, growth is available everywhere, so investors have many possible investment candidates. This is different from the pandemic period when growth was really only available in a few technology stocks. This move to more economically sensitive stocks is apparent in the strong performance of value stocks relative to their growthier brethren.

In addition to the shift to more economically sensitive stocks and sectors, consumer’s spending patterns are changing. Leaving the house means we need some new clothes, perhaps a size larger, at least temporarily. More importantly is that spending is shifting from stuff to help us survive the lockdowns to events and services. Like dogs off a leash, people have huge pent-up demand to go out to dinner or go on vacation. National restaurant chains are reporting they are once again operating at 100% of capacity. None of us has really had a vacation for more than a year, and many of us could really use some time off. My mother used to call for an occasional “mental health day,” but who wanted to take a day off to stay at home and stare at the television hoping, magically, that there was a new season of “The Queen’s Gambit” to stream. Demand for services is exploding.

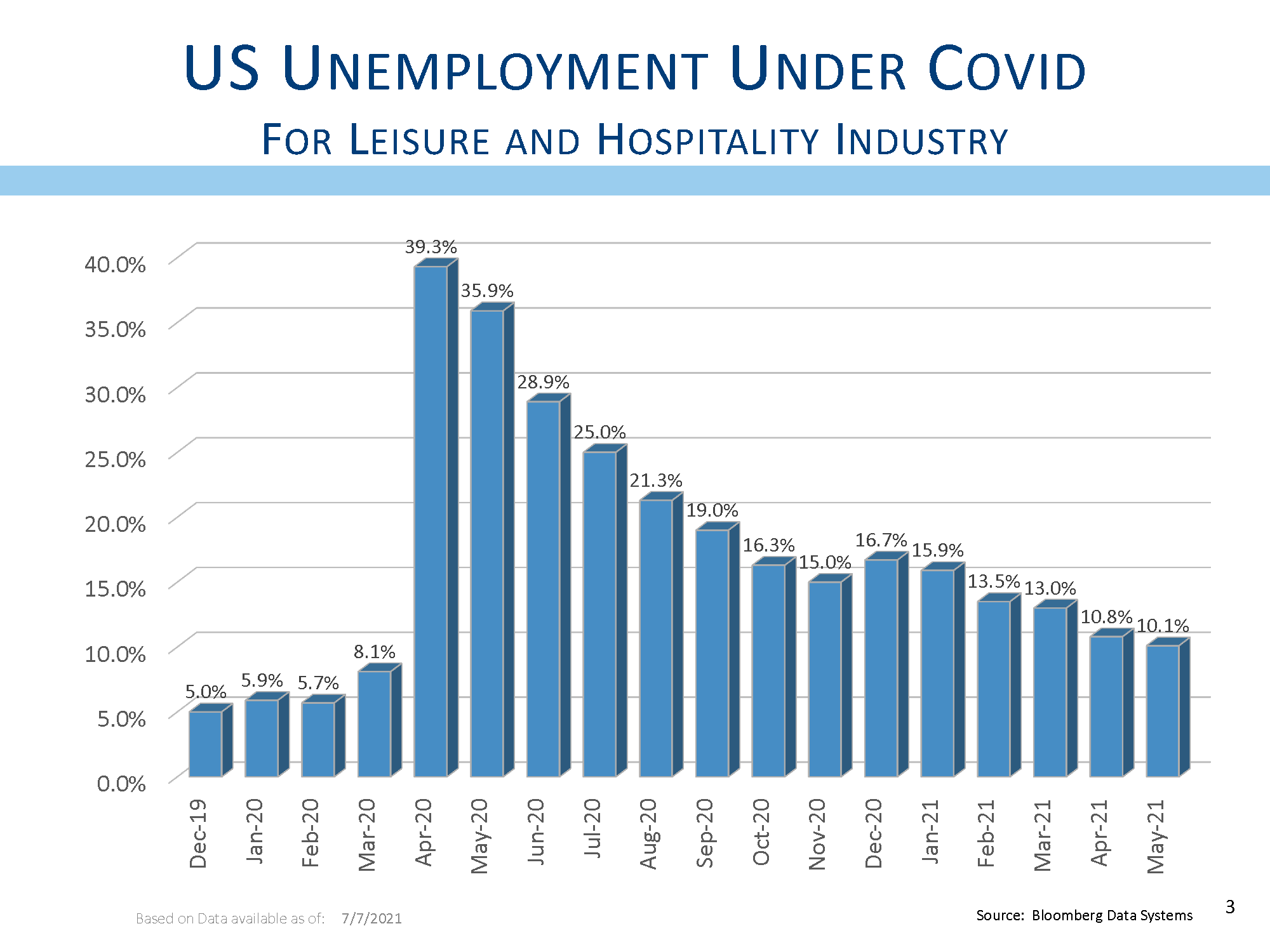

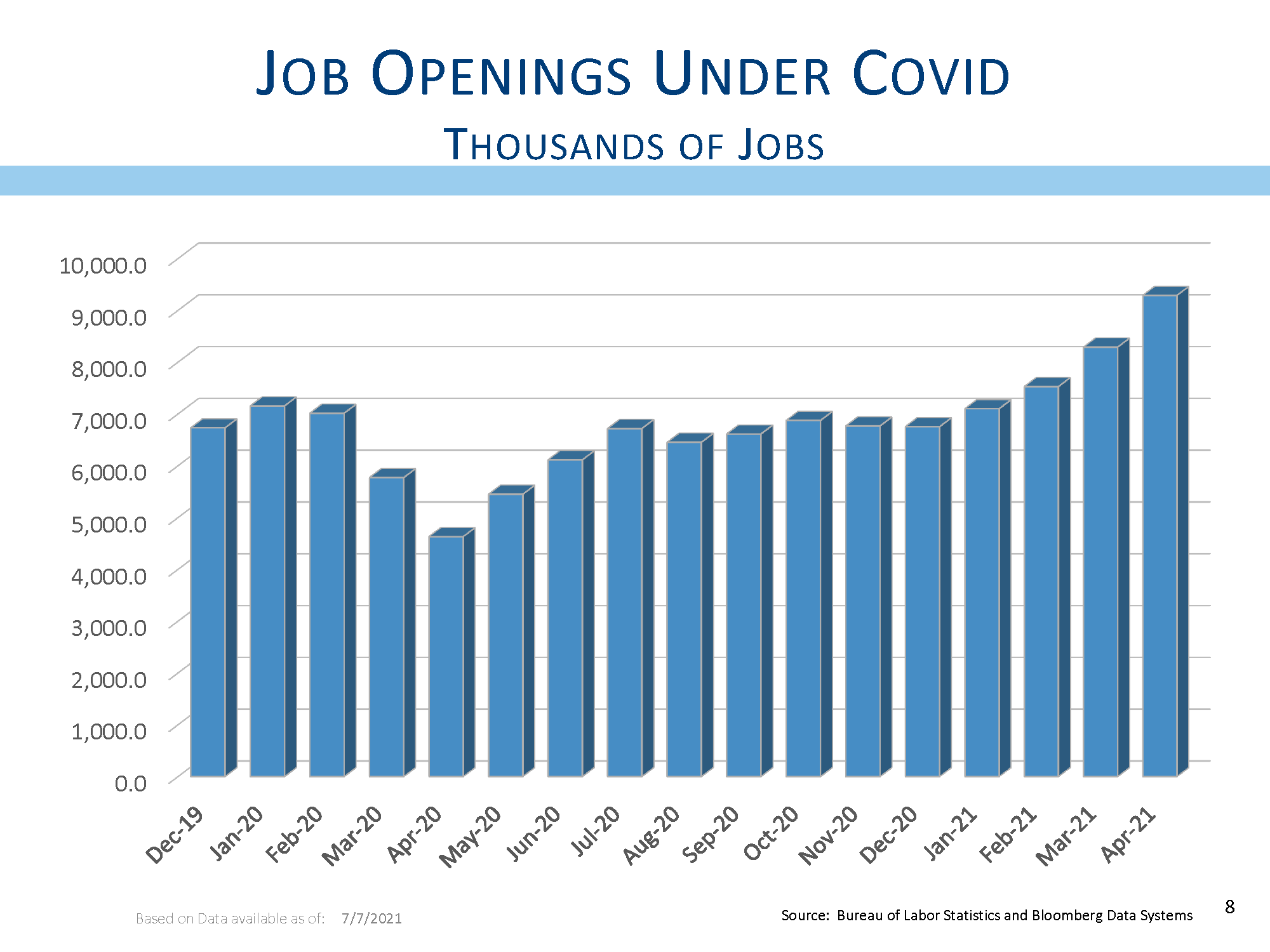

Therein lies the rub. Restaurants and hotels and other hospitality providers are struggling to get reopened. They are also struggling with an acute labor shortage. Many blame the supplemental unemployment benefits for the shortage of workers and there is certainly some truth to that. If you are able to make as much money on unemployment insurance as you could working as a busboy in a restaurant or as a barista at Starbucks, why would you work? This is a perfectly rational response, and is clearly one of the unintended consequences of the government’s policy to provide increased benefits to the millions of people who are out of work due to the pandemic.

Some states are eliminating their supplemental unemployment insurance benefits and unemployment rates in those states are declining. If jobs are readily available, do we really need to continue paying people not to work?

The reality is that there are worker shortages for many positions that pay significantly more than the minimum wage, so the increased unemployment insurance benefits are not the sole cause of the labor shortage. Baby boomers are retiring, and many have been forced to retire, perhaps earlier than they desired, as their jobs were eliminated during the pandemic shutdown. Other potential employees are struggling to arrange child care following more than a year with both children and parents at home. Still others have moved away from the big cities, trying to reduce Covid risks. There may simply not be the workers in the areas where the jobs are, especially now that restaurants and hotels are reopening.

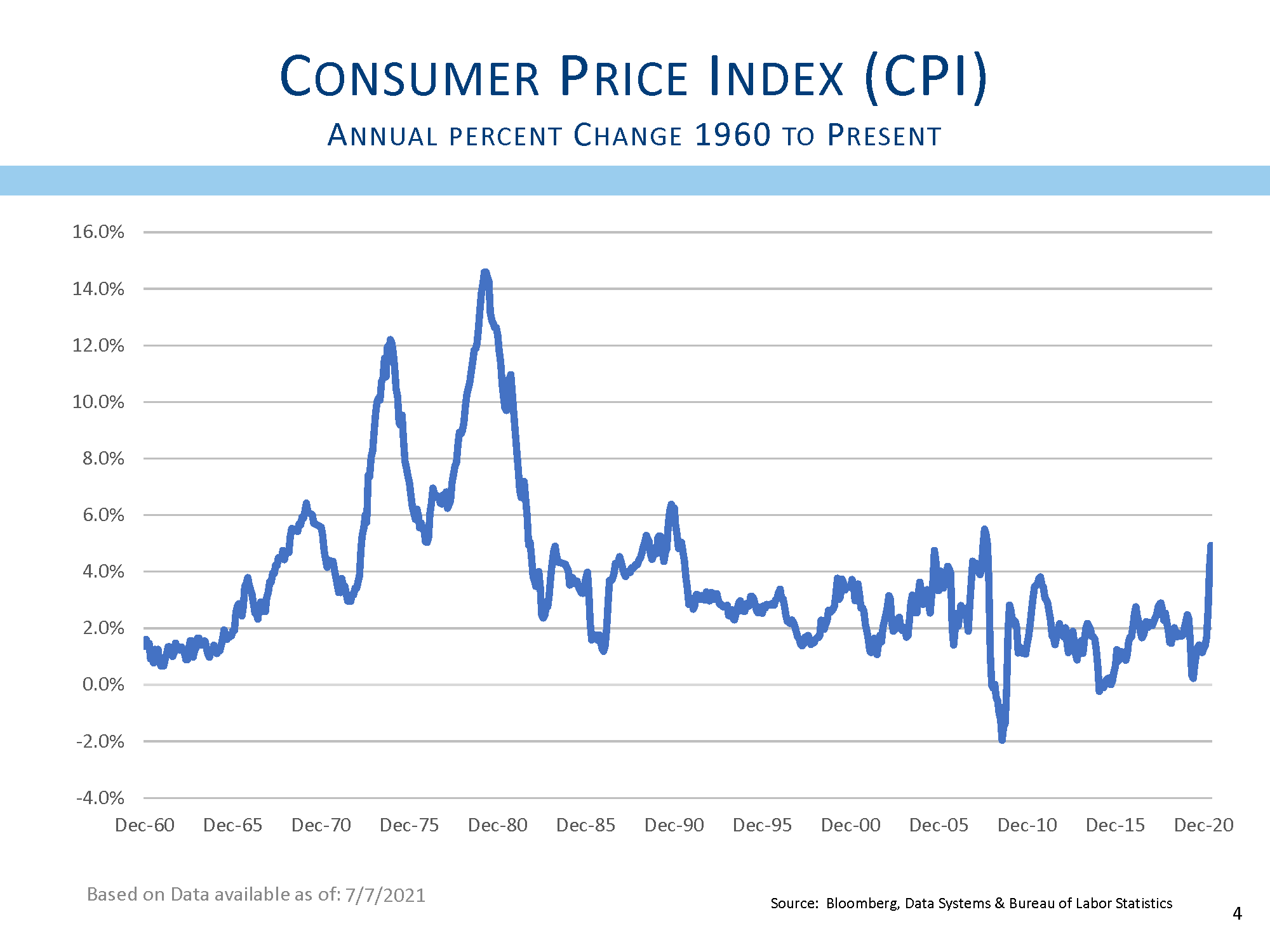

In order to attract workers, companies are offering signing bonuses and increased wages, and that is one factor contributing to the increases in inflation that have recently been reported. Like the labor shortage, there are myriad reasons for rising inflation, and as Chairman Powell suggested, many of these do not suggest inflation is on the verge of a 1970’s style spiral.

Inflation peaked at 14.8% in March of 1980, and other than a few short spikes, inflation has been below 4% since 1991. Many credit Fed Chairman Paul Volcker for killing the inflation dragon, and he certainly was instrumental in breaking the inflationary spiral. Volcker raised interest rates from 11.2% in 1979 to 20% in June of 1981, and inflationary pressures broke for decades. (So did the economy, as the U.S. fell into a severe recession in early 1980, and again from the summer of 1981 through the fall of 1982.) Paul Volcker ended his tenure as Fed Chairman in August of 1987, when inflation was just above 4%.

There are obviously many more factors at work that contributed to controlling inflation than just Paul Volcker’s leadership at the Fed, and many, but not all of those deflationary pressures, continue to this day.

The IBM PC was introduced in August of 1981, and the computer generation was upon us. When I started my own business, I remember that our first IBM PC XT cost a little over $3,000 each. Today you can walk into a Best Buy and walk out with a laptop for less than $1,000. Yes some models cost more, but many cost less. And on an inflation adjusted basis, a $3,000 computer in 1995 would cost $5,300 today.

Technology is deflationary. The cost of parts decline over time as more efficient manufacturing methods are introduced. And technology is ubiquitous. Remember that you have more computer power on your iPhone than was used by the astronauts of Apollo 11 to land on the moon. Technological deflation continues to exist and was not interrupted by the pandemic.

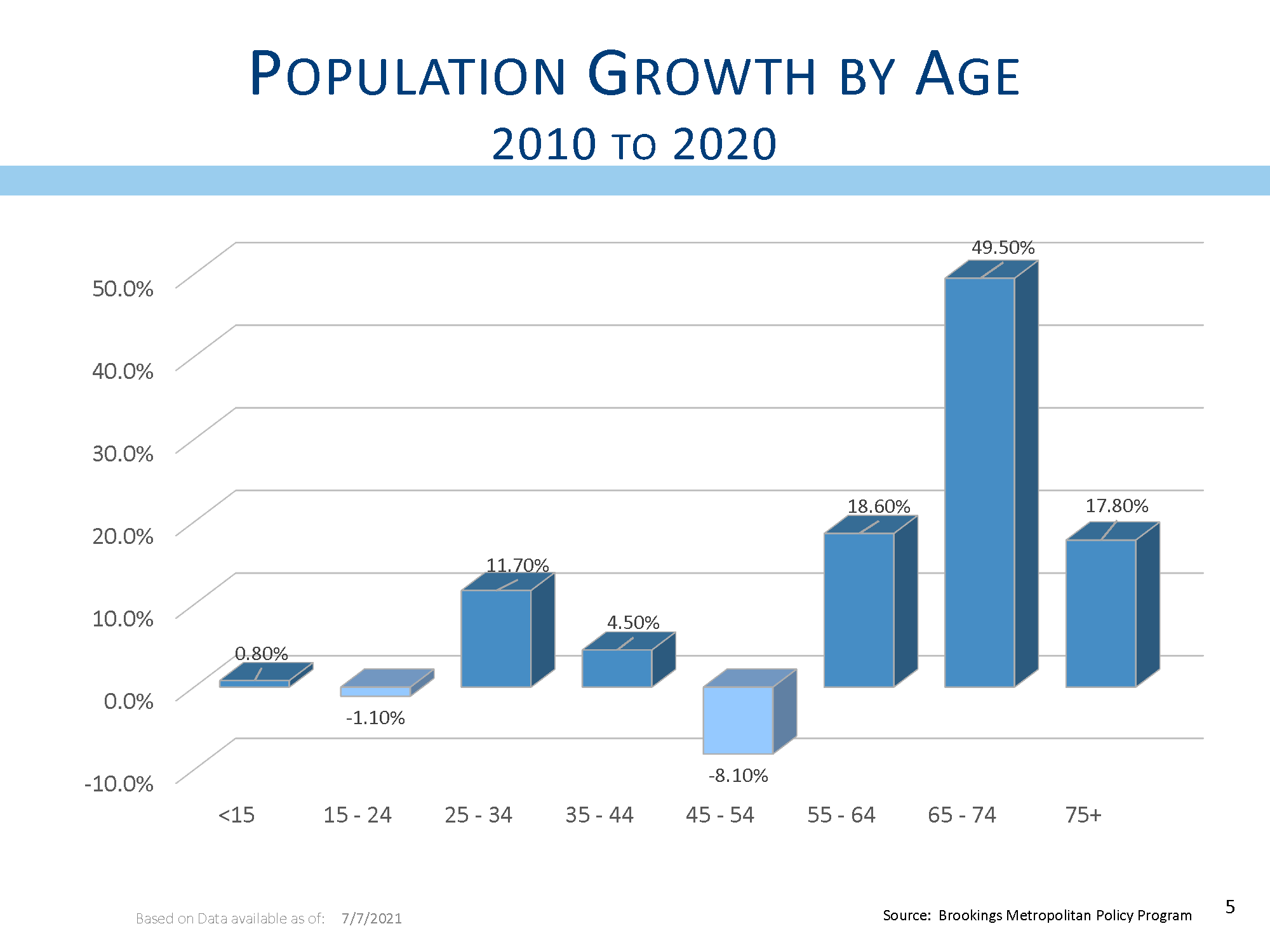

Demographics have also contributed to the sustained low rate of inflation. During the 1970’s, women began to return to the workforce. Women held many jobs during WWII when men were overseas fighting (remember Rosie the Riveter). Women began to go back to work when their Baby Boomer children were of sufficient age to care for themselves, allowing moms to consider restarting their careers. Families moved to the suburbs requiring a second car, and the homes in the burbs needed furnishings. Consumption demands were enormous as the second income in many households supported a huge expansion in purchasing power.

Many define inflation as too much money chasing too few goods, and that was certainly the case in the 1970’s. In many ways, however, the opposite is happening now. As we mentioned, many of those same Baby Boomers are retiring, and some have been forced to retire. As you move from receiving a paycheck to living off your savings, or a pension if you are lucky enough to have one, you must attempt to live within your means. More people retiring and living off their savings is not the kind of demographic shift that suggests there is too much money chasing too few goods.

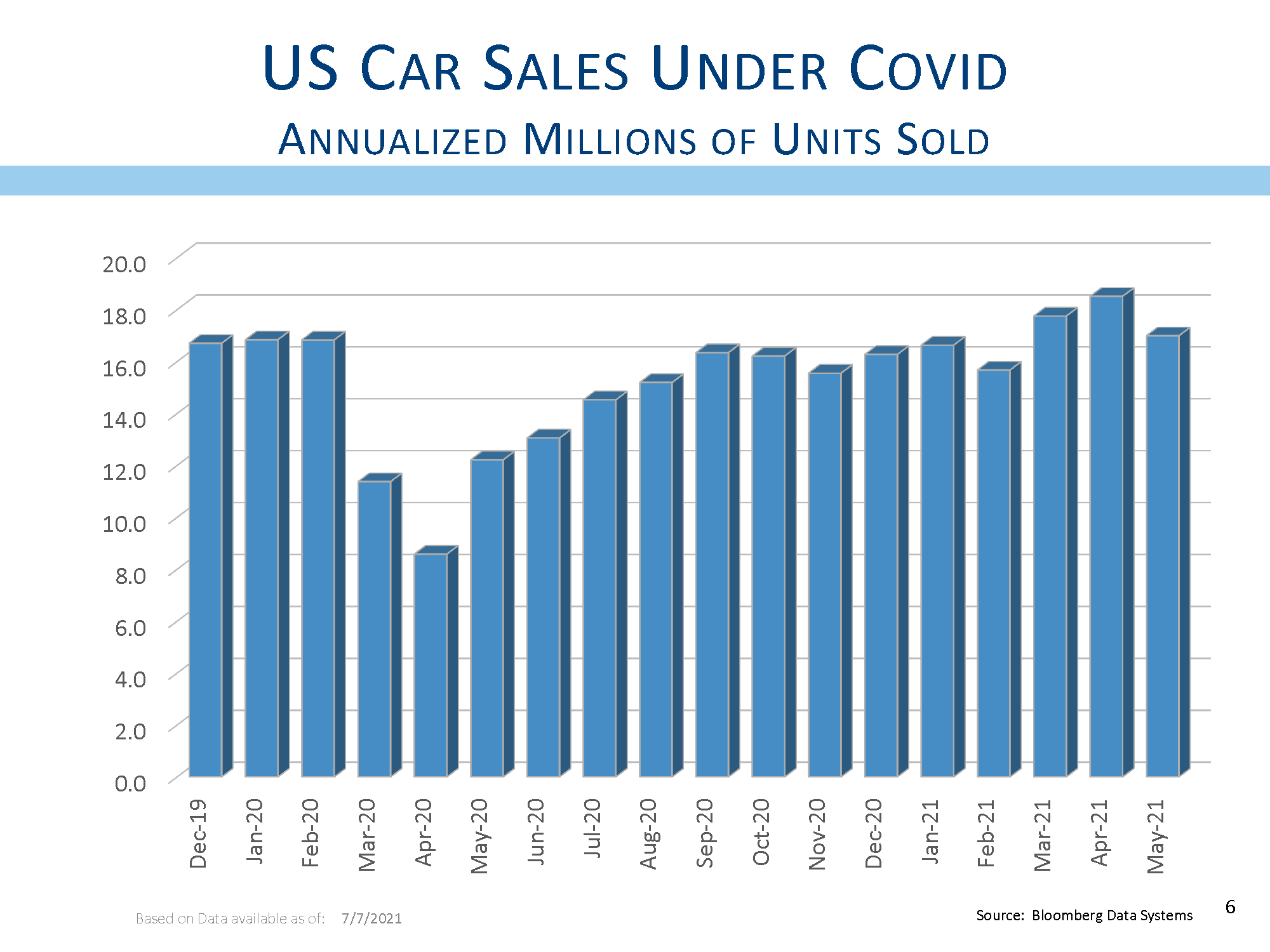

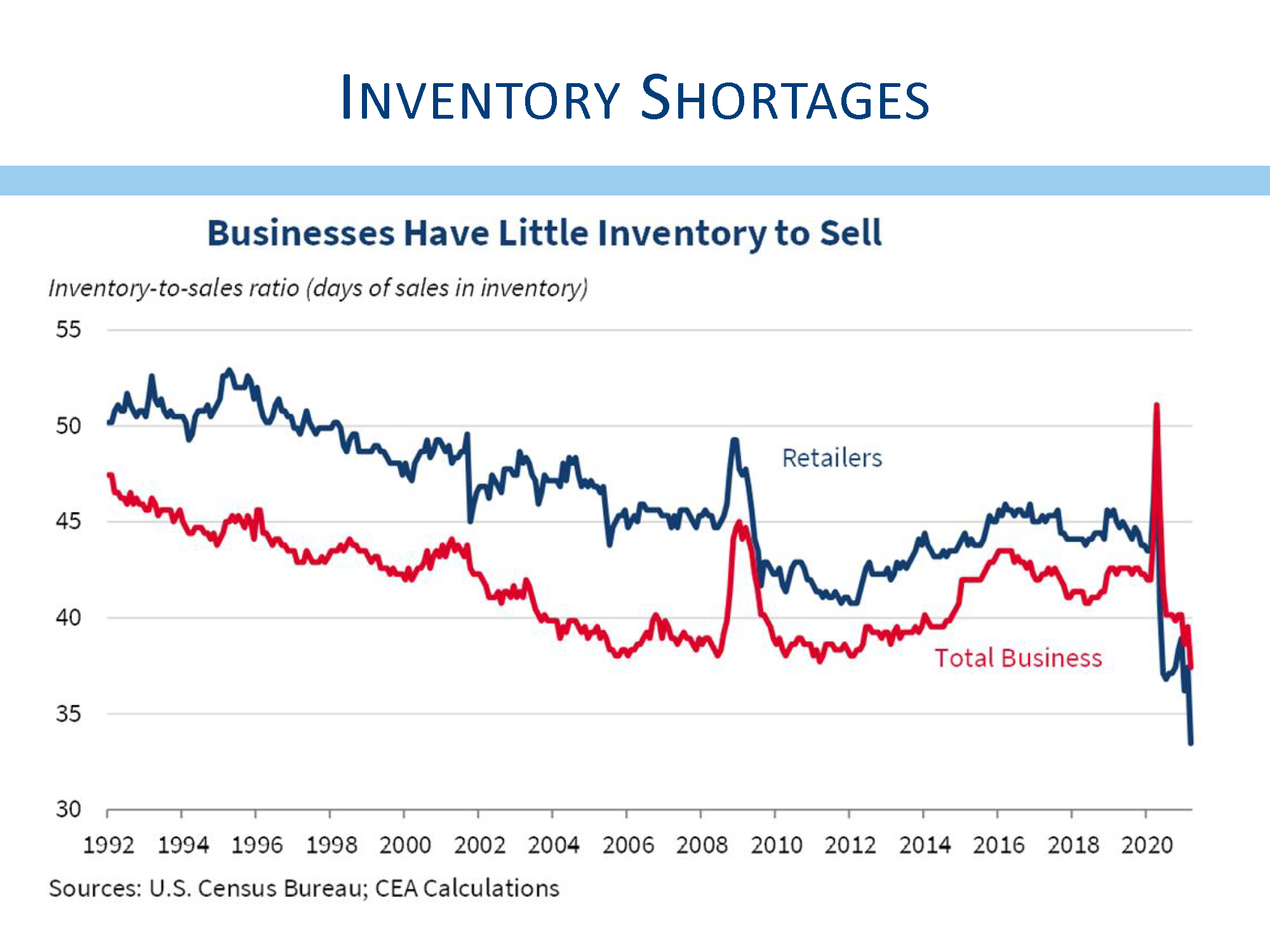

There are too few goods, and that is a function of lower production during the worst of the pandemic shutdown. Car manufacturers, thinking that new car demand would be modest, cut production and cancelled orders for supplies, including semiconductors. (As an aside, recall that the cost of semiconductors exceeds the cost of steel for new cars.) Car sales did not decline materially, and car dealers now find themselves short of inventory. In fact, many manufacturers across different industries are very short of inventory. As people are returning to more normal lives, there are not enough goods to meet the increased demand. Shortages exist in many areas.

If you are a manufacturer with too much demand and too few goods to sell, the only rational solution is to increase production. It may be impossible to acquire sufficient supplies in the short run, but given some time, manufacturers will increase production and shortages will diminish. While goods are in short supply, customers may have to pay up, and we see that with reports that consumers are paying more than the sticker price for new cars. This dynamic is certainly adding to inflationary woes. But how long will that continue? As supply shortages lessen, and as production increases, prices will return to normal. Production shortages are a short-term consequence of reopening after the pandemic shutdowns. This is not a long-term problem, and as production and prices return to normal, inflation pressures will diminish.

The dynamic with respect to labor costs is similar, although a shortage of workers may be harder to solve than a shortage of parts. Workers are acting rationally by maximizing their personal income, especially if that means staying home and collecting enhanced unemployment benefits. But those unemployment benefits end in September, and then the number of people willing to take a job as a busboy or barista is likely to increase. In the short run, companies that are having trouble finding workers are being forced to pay more. That is adding to inflationary pressures. What happens after September? For low-wage jobs, as the number of available candidates increases, the pressure to pay more will be reduced. Further, if your company just paid more for a worker than you wanted to pay, how likely are you to give that worker a big raise next year? Wage pressures exist, but we do not expect it will lead to an inflationary spiral over the next several years.

For the higher compensated and skilled workers ,who are also in short supply, it may mean that workers will need to be retrained, and that too will add to payroll costs. Some recent retirees may be encouraged to come back from retirement and rejoin the workforce. Other people may be encouraged to move back into cities where jobs exist. Companies too must change. Those companies that embrace a hybrid working schedule, by letting people work from home part of the time, are likely to attract some of the best and brightest. Inflationary pressures here may also abate, although these could take longer to resolve.

One area where inflationary pressures are likely to continue arises from changes to global supply chains. Technology and logistics have enabled companies to source parts from the low-cost producer anywhere in the world. Many manufacturers have also embraced a “just-in-time” inventory system where parts are delivered right as needed, eliminating the need for companies to stockpile supplies. Inventory sitting on shelves ties up corporate funds and reduces returns, and companies have gotten very efficient at running with minimal surplus goods.

What happens when the 2-cent swab, sourced from China, and used to complete a Covid test, is no longer available? Should medical testing be delayed because the swabs are in short supply? Does it make more sense to have a second source for swabs, or perhaps the entire supply chain needs to be reimagined. Perhaps the swabs should come from a local manufacturer to prevent delaying the completion of medical tests. One of our portfolio managers called the reimagination of global supply chains “USA 2.0,” and there are potential investment opportunities that will be derived from securing secondary supplies for all components no matter how important.

Just-in-time inventory systems may be replaced with a “just-in-case” attitude. Having a few extra supplies may help when demand picks up, and customers are willing to purchase more goods if the manufacturers can produce them.

Both the reimagining of supply chains and the move to a just-in-case inventory system suggest that globalization may have peaked. We have learned to be more suspect of seeking out the lowest-cost producer no matter the risks. Globalization has been one of the trends that have helped keep inflation low, and the reversal of that trend suggests some inflationary pressures will exist beyond when pandemic-slowed production returns to normal.

Another area for concern regarding the potential for inflationary pressures is that many central banks seem less willing to aggressively fight inflation. The Fed, sighting the many years where inflation has run below their 2% target, suggested they would permit inflation to run above 2% for some time so that inflation averages 2% over the entire business cycle. If central bankers lose the resolve to fight inflation, that suggests that inflation will become far more entrenched before central bankers decide to act. That will make inflation much harder to contain, and is a risk we will continue to monitor.

While we watch the Fed’s inflation response carefully, we must also acknowledge the extraordinary action they took early in the pandemic. As the economy started to shut down, companies started losing access to financial markets in order to raise funds. Some companies were trying to survive while others were trying to fund the growing demand for their goods and services. A health-care crisis looked as if it would very shortly also become a financial crisis. That further spooked financial markets and added downward pressure to falling stock and corporate bond prices.

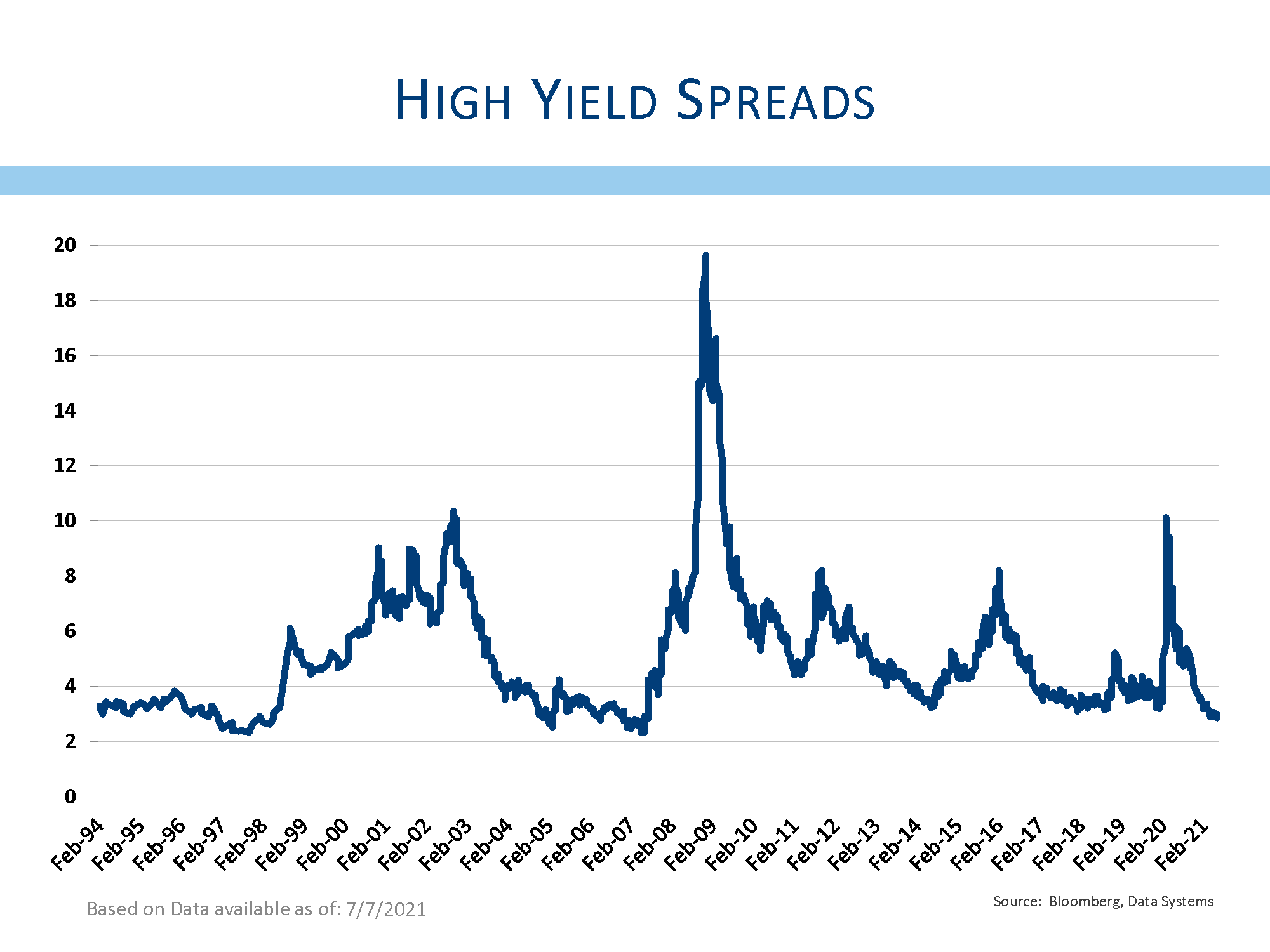

The Fed, taking a lesson from the Great Financial Crisis, acted quickly and decisively. They revived several programs designed more than a decade ago and pumped massive liquidity into the system. Their resolve was instrumental in preventing another financial crisis. There is an old adage that investors should “never fight the Fed,” and this was one time where that adage was exceptionally profitable. Some may argue that the Fed no longer needs to provide support to financial markets, especially by purchasing mortgage bonds when the housing market is so strong. Still, the Fed’s actions at the beginning of the pandemic were instrumental in laying the groundwork for the strong recovery we are seeing today. Further, the lack of any problems in credit markets is testament to how effective their actions have been.

In just six short months, we have gone from full pandemic lockdown to strong economic recovery. We would expect that other countries can accomplish the same thing, and hope that many other nations will be solidly on the road to recovery by the end of this year. This suggests an investment opportunity as those economies transition from pandemic to economic expansion.

With the Fed holding interest rates low, with credit markets well-behaved, and with expectations for strong corporate earnings, we see little that makes us exceptionally nervous. Yes, markets correct regularly, and yes many valuation measures are at or near record highs, but risks seem quite moderate at this time. Markets love to climb “the wall of worry,” and investor complacency may be one of the bigger risks investors face right now. We also worry about another pandemic lockdown, and are concerned that our pandemic fatigue might make controlling another outbreak that much more difficult. The best way to avoid another outbreak is for everyone to get vaccinated. That will help everyone stay healthy, and will provide legs to the economic expansion already underway.

Everyone at L&S continues to work tirelessly to make sure that we meet or exceed your needs. If you have any questions or concerns, or if your investment objectives have changed in any way, please contact us. Stay well, stay safe, and stay sane.

Bennett Gross CFA, CAIA

President

L&S Advisors, Inc. (“L&S”) is a privately owned corporation headquartered in Los Angeles, CA. L&S was originally founded in 1979 and dissolved in 1996. The two founders, Sy Lippman and Ralph R. Scott, continued managing portfolios together and reformed the corporation in May 2006. The firm registered as an investment adviser with the U.S. Securities and Exchange commission in June 2006. L&S performance results prior to the reformation of the firm were achieved by the portfolio managers at a prior entity and have been linked to the performance history of L&S. The firm is defined as all accounts exclusively managed by L&S from 10/31/2005, as well as accounts managed in conjunction with other, external advisors via the Wells Fargo DMA investment program for the periods 05/02/2014, through the present time.

L&S claims compliance with the Global Investment Performance Standards (GIPS®). L&S has been independently verified by Ashland Partners & Company LLP for the periods October 31, 2005 through December 31, 2015, and ACA Performance Services for the periods from January 1, 2016 to December 31, 2020. Upon request to Sy Lippman at slippman@lsadvisors.com. L&S can provide the L&S Advisors GIPS Report which provides a GIPS compliant presentation as well as a list of all composite descriptions. GIPS® is a registered trademark of CFA Institute. CFA Institute does not endorse or promote this organization, nor does it warrant the accuracy or quality of the content contained herein.

L&S is a registered investment adviser with the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission (“SEC”) and is notice filed in various states. Any reference to or use of the terms “registered investment adviser” or “registered,” does not imply that L&S or any person associated with L&S has achieved a certain level of skill or training. L&S may only transact business or render personalized investment advice in those states and international jurisdictions where we are registered, notice filed, or where we qualify for an exemption or exclusion from registration requirements. Information in this newsletter is provided for informational purposes only and should not be construed as a solicitation to effect, or attempt to effect, either transactions in securities or the rendering of personalized investment advice. Any communications with prospective clients residing in states or international jurisdictions where L&S and its advisory affiliates are not registered or licensed shall be limited so as not to trigger registration or licensing requirements. Opinions expressed herein are subject to change without notice. L&S has exercised reasonable professional care in preparing this information, which has been obtained from sources we believe to be reliable; however, L&S has not independently verified, or attested to, the accuracy or authenticity of the information. L&S shall not be liable to customers or anyone else for the inaccuracy or non-authenticity of the information or for any errors of omission in content regardless of the cause of such inaccuracy, non-authenticity, error, or omission, except to the extent arising from the sole gross negligence of L&S. In no event shall L&S be liable for consequential damages.

L&S’ current disclosure statement as set forth in ADV 2 of Form ADV as well as our Privacy Notice is available for your review upon request.