April 7, 2017

“The simple message is the economy is doing well…We have confidence in the robustness of the economy and its resilience to shocks…We’re operating in an environment where the U.S. economy is performing well and risks seem pretty balanced. I think people can feel pretty good about the economic outlook.”

– Federal Reserve Chair Janet Yellen, March 15, 2017

The irony of the Fed’s decision to raise interest rates, accompanied by Yellen’s fairly positive statement, is our concern that risks were, in fact, rising at that time. We are not suggesting in any way that the systemic risks are worrisome or that a recession is around the corner, but we do worry that risks are somewhat higher than they have been since the election of Donald Trump.

The election of Mr. Trump ushered in a changed investment environment. Investors believed that the new administration would quickly reduce regulation, lower taxes, spend heavily on infrastructure, and repeal and replace Obamacare. Each of those campaign promises have important investment implications, and the sectors that were impacted by those promises began to improve virtually the second the election results were known.

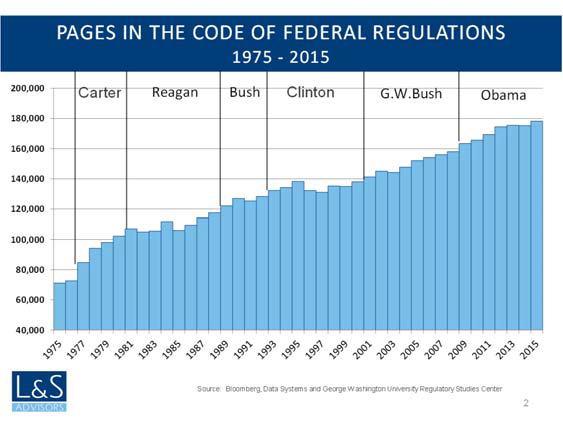

The promise of lower regulation was instrumental in pushing the performance of the financial services sector to the top of the heap since the presidential election. Financial companies have been burdened with regulations that have been piled upon regulations for decades. There are anti-money laundering regulations, anti-terrorist regulations, Dodd-Frank and Volker rules, SEC rules, CFTC rules, FINRA rules, Office of the Comptroller of the Currency rules, FDIC rules, Federal Housing Finance Authority rules, and the new Consumer Financial Protection Bureau rules. Most of these regulations are well-meaning, and many are effective at protecting consumer interests, but the burdens have grown and grown, and the costs of understanding and abiding by these regulations has become extreme. The promise of fewer regulations, and perhaps even the potential for less-attentive enforcement of these regulations, was one of the primary factors pushing financial stocks higher. Any reduction in the cost of regulation would fall directly to the bottom line, and many investors believed that relief for these companies was finally at hand. Stock prices almost immediately reflected the potential for higher earnings coming from a more friendly regulatory environment.

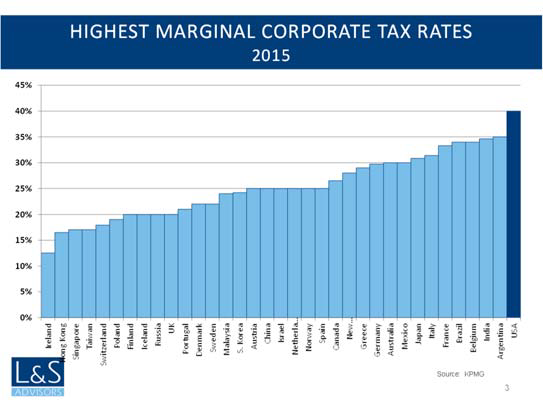

In addition to lower regulation, investors were also enamored with the prospects for lower taxes. Analysts were quick to identify those companies with the highest effective tax rates, and the commensurate increase in earnings that would follow any change in corporate tax rates. Corporate tax rates in the United States are the highest in the developed world, and any reduction in those rates would make America more competitive on a global scale. While it is true that many companies, particularly the large multi-national corporations, pay much lower taxes than the highest posted rates, any reduction in tax rates would be welcomed by corporate America.

Tax policy is one of those complex political animals that have some of the highest unintended consequences. For example, consider the luxury tax placed on the purchase of new yachts several years ago. Why not tax the cost of very high-end boats? This tax falls solely on the very wealthiest of individuals, those that can easily afford to contribute more. It seems like such a logical alternative. The unintended consequence was that wealthy people stopped buying new boats and instead refurbished existing yachts where there was no luxury tax. As new yacht sales dropped toward zero, so too did employment at boat-building yards. A tax on high-end boats caused employment to decline for blue-collar boat builders. How is that for unintended consequences!

The market impact of taxes is to generally encourage less production or consumption of that item being taxed. We tax cigarettes so that fewer cigarettes are consumed. The same with liquor taxes. Why, some people ask, would the government want to tax incomes? Who wants lower incomes?

Arthur Laffer, an economist for the Reagan administration, came up with the thought process now bearing his name, the Laffer curve. His thought process suggests that as tax rates are raised, revenues may actually decline. Consider tax rates that are 100% of income. A confiscatory tax that high would mean there would be zero revenue collected by the government because no one would work. Who would put in the effort to work when all of the proceeds would be collected by the government? Laffer’s idea is one of the cornerstones of Supply-Side economics. Raising tax rates could actually lead to lower, not higher revenues.

We are all for a simplification of tax codes, and the lack of credence paid to Steve Forbes flat-tax seems more poignant with each passing day. The problem is designing tax rules that provide the incentives we desire without the unintended consequences we seek to avoid. The other problem with redesigning the tax code is trying to determine what the impact on revenue will be. Baseline forecasts imply holding everything else constant and only changing the tax rates. However, we know from past experience that holding everything constant ignores the pending unintended consequences, some of which might be positive. The current administration is arguing for the need for dynamic forecasts, that is revenue estimates that incorporate a higher economic growth rate because of the incentives from lower taxes. The truth of the matter is that citizens work hard to legally reduce their personal tax bill, and it is very hard to know with any precision what the impact on revenue will be from any tax revision.

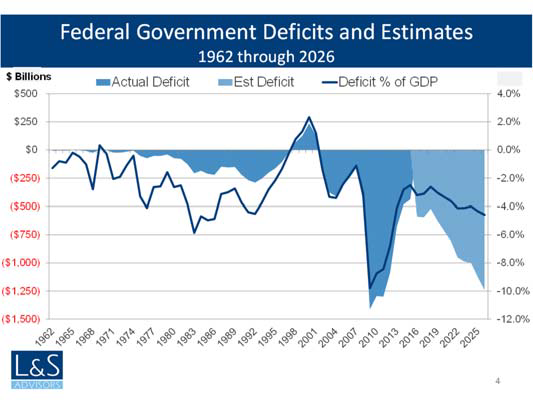

Adding to this complexity is the fact that many budget conscious citizens do not want to see the federal deficits increased. Tax cuts that end up reducing the revenues collected will therefore cause budget deficits to expand. Budget deficits are not that threatening today, but future forecasts do not look promising. As citizens age, their incomes decline while their need for social services tends to increase. The estimates of future deficits are somewhat discouraging, and the need for more budget restraint is omnipresent.

The current administration has promised to make any revision to the tax code “revenue neutral.” That means the amount of revenue collected will be unchanged, so that tax code revisions will not add to our deficits. This is a wonderful goal, but it has implications that may not be fully recognized by stock markets. If tax code revisions are revenue neutral, then there will be winners and losers. Some companies will pay more while others will pay less. The net result is that there will be, at best, a very modest increase in the earnings of corporate American. If some of the recent gains in the stock market are based on the prospects for higher earnings due to lower taxes, then the market may, in fact, be overestimating Trump’s positive influence. This is a risk that seems more apparent than it was immediately following the election.

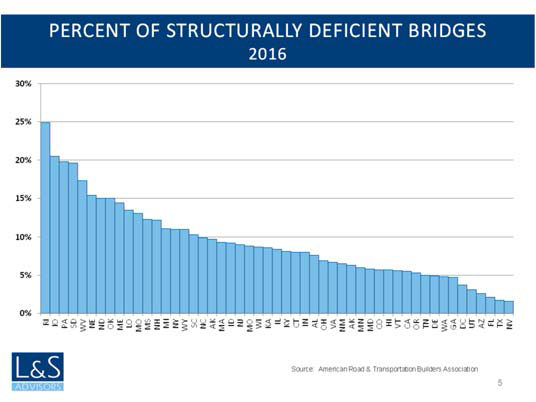

Infrastructure is another one of those market sectors that has performed well since the presidential election. The potential benefits are being pushed into the future, and stock prices may be somewhat ahead of themselves. Both candidates promised to spend heavily on improving America’s infrastructure, and the Trump administration has recently voiced its desire to spend $1 trillion over the next decade.

It is no secret that our bridges and highways are aging, and too much maintenance has been delayed for far too long. Our air traffic control system is woefully behind that of many other companies. Our cellular system is not as advanced as those in Japan and in parts of Europe. France and Japan have had fast trains for decades, and even China’s fastest trains far exceed the speed attainable on America’s aging tracks.

There are worthy projects that need attention, and society would benefit from many of them. Of course, the political spoils of spending heavily on infrastructure are hard to avoid, and it is likely we will get some bridges to nowhere just to please some political constituency somewhere.

Many economists believe it was more appropriate to spend heavily on infrastructure when the economy was struggling to recover from the Great Recession, but it is much more difficult to justify government spending on these projects when the economy is doing well.

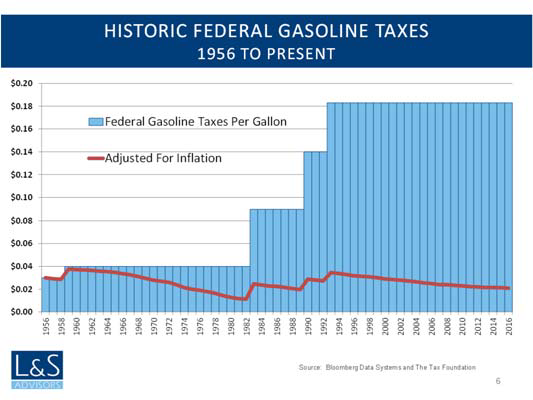

Adding insult to injury is the fact that any spending program is unlikely to generate much revenue to support not just the construction of these projects, but also the necessary continuing maintenance. An air traffic control system could be supported by flight taxes, and highways and bridge construction could be supported by increased gasoline taxes, as originally intended when Eisenhower created the Interstate Highway System. Regrettably, the hue and cry preventing any increase in gasoline taxes is part of the reason why we find our roads in such a state of disrepair. Gasoline taxes have not been increased since 1993, and the system finds itself unable to meet its current obligations.

Intelligently conceived infrastructure projects that have funding sources would be a plus for our society. However, infrastructure that is unsupported by any revenue steam, and simply raises the deficit, is unlikely to be in the country’s best long-term interest. As the political realities of infrastructure spending are confronted, it seems likely that any infrastructure spending bill will be postponed, and may not have any positive impact in 2017. Stocks with higher earnings estimates based on this spending starting in 2017 could be poised for some near-term disappointment.

As we have seen in recent weeks, the Republican plan to replace Obamacare with something better and less expensive failed to gain any traction, and was pulled from the House before an embarrassing vote could be completed. Healthcare reform is a very difficult issue, and the statement from Mr. Trump that “nobody knew that health care could be so complicated’ seems naïve at best. This is the inherent problem with entitlements—people like them, and once you provide them, people do not want to give them up, even if they were against the very notion of that entitlement just weeks before.

While the investment implications of the failed repeal of Obamacare are more difficult to determine, the fact that the Republican house could not agree on a plan suggests that other parts of the Trump agenda may be delayed or stopped by political infighting not just between parties, but also from within the Republican party as well.

Deficit hawks could fight infrastructure and tax reform based on their likely potential to increase the deficit, and it may be that other promises made during the campaign will find a similar fate as the repeal and replacement of Obamacare. This is a risk for the markets that was not prevalent a few weeks ago.

In the period following the election, we saw a change in the stock markets psyche. Prior to the election, the market had been dominated by the concept that the “new normal,” that is very slow growth, was here to stay for the foreseeable future. As the third quarter of 2016 ended, and as the run-up to the presidential election progressed, the market began to embrace the idea that the “new normal” could be ending, and more robust growth was ahead.

More robust growth would come with faster inflation, and the “reflation” trade since the election was characterized by modestly rising interest rates, rising oil and commodity prices, lower credit spreads, and a stronger U.S. dollar. Industrials, materials and other more cyclically-oriented sectors were outperforming, while the more conservative, slower growth sectors such as consumer staples, utilities and telecommunications were lagging.

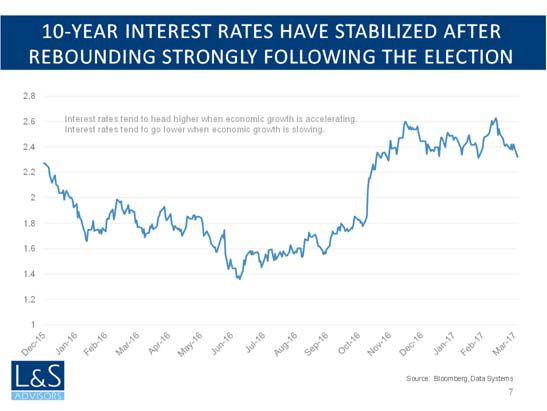

The character of the market started to change right around the time that the Fed raised interest rates for the second time in three months. 10-year interest rates had increased to about 2.6% in response to the Fed’s move, but interest rates quickly began to decline, and as of this writing, the yield on the 10-year note was down to 2.35%. Why were interest rates falling in a reflationary environment? That did not make sense.

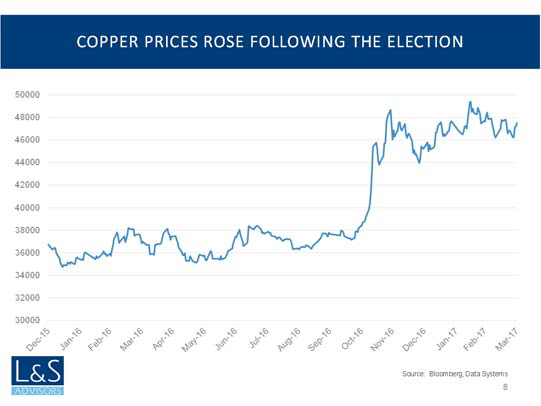

Adding to the unease was a steady drop in copper prices. Copper is often referred to as “Dr Copper” because it is a good indicator of the strength of the economy. Electricity runs on copper, and economies cannot expand without copper and without electricity. The price of copper dropped about 6.5% from the recent highs. This is not indicative of an economy that is poised to accelerate its growth.

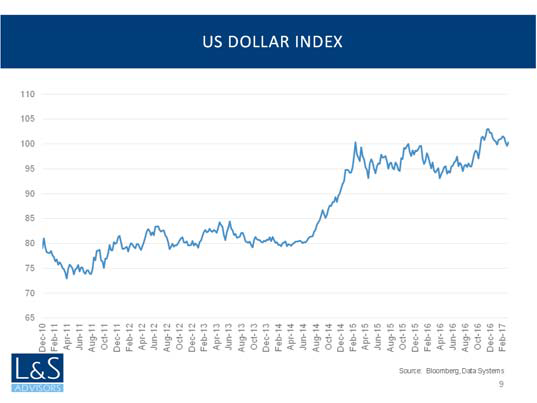

The U.S. dollar had also been strengthening since before the election. The stronger dollar reflected rising interest rates here at home and an “America First” mentality. After reaching a high near the end of the year, the dollar declined by about 4% in the first calendar quarter. Why was the dollar falling when the Fed was raising interest rates and economic growth was supposed to be rebounding?

Nearly all of the signs of the reflation trade showed signs of reversing just as the Fed raised interest rates. Not only did longer-maturity interest rates fall, but so did the dollar, oil, and other commodity prices, while credit spreads began to widen out. The signals coming out of the economy were not completely supportive of the continuation of the reflation trade. This is somewhat disconcerting and causes us to be slightly more cautious.

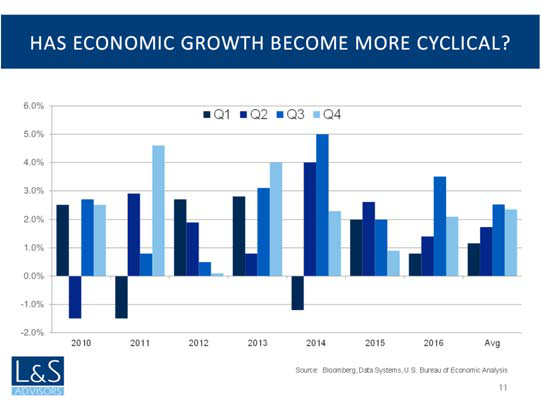

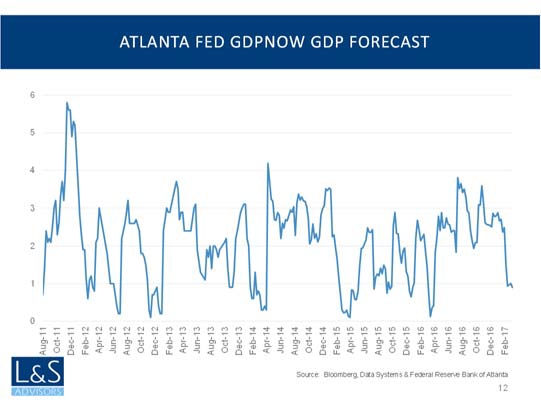

It seems that economic growth has been particularly weak during the first calendar quarters since the end of the Great Recession. We do not have an explanation as to why that is occurring. Certainly some particularly harsh winters have pulled activity from the winter into the spring. Yet for much of the country, this winter was fairly mild, and yet the Atlanta Fed is currently indicating that economic growth is running at only about 1%, down from the 2.1% reported during the fourth calendar quarter. This is the lowest reading since April of last year. Why is first quarter growth weak again?

An analysis of the numbers does support the conclusion that the first quarter has been the weakest calendar quarter of the years following the Great Recession, so perhaps this year is no different. Perhaps the seasonal adjustments need to be reworked, or perhaps the economy has grown more seasonal. At first glance, this does not make sense since we are more of a service-oriented economy, and the demand for services should not necessarily be impacted by the time of the year.

Wouldn’t it be great if Donald Trump could use one of his handy executive orders and mandate that growth will be 3-4% for the rest of his administration. That would certainly solve a lot of problems. With faster growth would come modestly higher interest rates, higher corporate profits, higher tax revenues and the complementary lower deficits. If only it were that easy.

The President must now consider his own “Hippocratic oath” to our country to “do no harm.” He must do everything in his power to help America grow, to rebuild our tired infrastructure, and to help us face the political and social problems of the upcoming 21st century. By nearly all measures, this does not mean the passage of a “border adjustment tax” (BAT) or the prevention of immigration into this great country of ours.

It seems clear to most economists that a border adjustment tax is nothing more than a protectionist tariff, the kind that exacerbated the pain of the Great Depression. According to definitions from the World Trade Organization, “tariffs give a price advantage to locally-produced goods over similar goods which are imported, and they raise revenues for governments.” Nothing more needs to be said. Perhaps Mr. Trump will negotiate the U.S out of the World Trade Organization when the WTO declares a BAT illegal on the playing field of free trade. It does seem that most republicans and democrats alike are moving away from the BAT, and this is a very good thing.

Likewise, an immigration policy that prohibits people from immigrating to the United States will likely slow the growth of our country, just at a time when we need more growth, not less.

Market risks have increased, due in part to the fact that Trump’s policies may be delayed for some time. We do need pro-growth policies, and the hopes that came with the election of a more populist President seem to have been postponed. That is a shame for all of us.

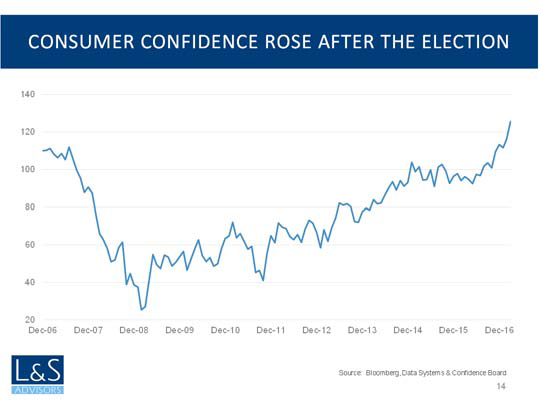

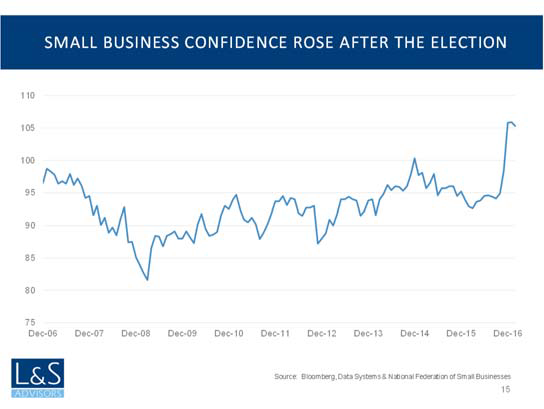

When we assess the health of markets, we look for three things. First, we want to see interest rates gently moving up, which we see as a confirmation of stronger economic growth ahead. Interest rates have moved materially higher since last June, even as they have backtracked somewhat over the past couple of weeks. Further, we look for stronger corporate earnings which, again, confirms stronger economic growth. Here again, the news is relatively positive. Corporate earnings are poised to grow in 2017, even as earnings have been fairly stagnant for quite some time. Lastly, we look for improved confidence as a sign that the growth in the economy can be sustained. Here the news is quite positive. Both consumer confidence and small business confidence have improved smartly since the election, and are now at levels higher than were prevalent prior to the start of the Great Recession. This is very important and helps us mitigate our concerns.

With regard to the next recession, our best indicators are the shape of the interest rate curve, called the yield curve, and the growth of the index of Leading Economic Indicators (LEI). On both of these metrics, we find no evidence that a recession is on the near-term horizon. These two metrics have been successful at forecasting the next recession roughly three to six quarters ahead. This suggests that it is unlikely we will see a recession in 2017, or into the first part of 2018.

Risks may have increased somewhat. We do acknowledge that markets may be slightly ahead of themselves, especially as some policy initiatives are pushed back into 2018. Further, we recognize that valuations are not inexpensive. Still, we have tremendous confidence in our ability to survive a divided government, and we will survive a modest increase in risks. We would prefer to thrive, but that is sometimes dependent on things that are out of our control.

As always, it is important that we know of any changes in your financial situation. Please feel free to call us if you have any questions or comments regarding your investment portfolio.

Bennett Gross CFA, CAIA

President

L&S Advisors, Inc. (“L&S”) is a privately owned corporation headquartered in Los Angeles, CA. L&S was originally founded in 1979 and dissolved in 1996. The two founders, Sy Lippman and Ralph R. Scott, continued managing portfolios together and reformed the corporation in May 2006. The firm registered as an investment advisor with the U.S. Securities and Exchange commission in June 2006. L&S performance results prior to the reformation of the firm were achieved by the portfolio managers at a prior entity and have been linked to the performance history of L&S. The firm is defined as all accounts exclusively managed by L&S from 10/31/2005, as well as accounts managed in conjunction with other, external advisors via the Wells Fargo DMA investment program for the periods 05/02/2014, through the present time.

L&S claims compliance with the Global Investment Performance Standards (GIPS®). L&S has been independently verified for the periods October 31, 2005 through December 31, 2015. Upon a request, L&S can provide the L&S Advisors GIPS Annual Disclosure Presentation which provides a GIPS compliant presentation as well as a list of all composite descriptions.

L&S is a registered investment adviser with the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission (“SEC”) and is notice filed in various states. Any reference to or use of the terms “registered investment adviser” or “registered,” does not imply that L&S or any person associated with L&S has achieved a certain level of skill or training. L&S may only transact business or render personalized investment advice in those states and international jurisdictions where we are registered, notice filed, or where we qualify for an exemption or exclusion from registration requirements. Information in this newsletter is provided for informational purposes only and should not be construed as a solicitation to effect, or attempt to effect, either transactions in securities or the rendering of personalized investment advice. Any communications with prospective clients residing in states or international jurisdictions where L&S and its advisory affiliates are not registered or licensed shall be limited so as not to trigger registration or licensing requirements. Opinions expressed herein are subject to change without notice. L&S has exercised reasonable professional care in preparing this information, which has been obtained from sources we believe to be reliable; however, L&S has not independently verified, or attested to, the accuracy or authenticity of the information. L&S shall not be liable to customers or anyone else for the inaccuracy or non-authenticity of the information or for any errors of omission in content regardless of the cause of such inaccuracy, non-authenticity, error, or omission, except to the extent arising from the sole gross negligence of L&S. In no event shall L&S be liable for consequential damages.

The S&P 500 index is a free-float market capitalization weighted index of 500 of the largest U.S. companies. The index is calculated on a total return basis with dividends reinvested and is not available for direct investment. The composition of L&S’ strategies generally differs significantly from the securities that comprise the index due to L&S’ active investment process and other variables. L&S does not, and makes no attempt to, mirror performance of the index in the aggregate, and the volatility of L&S’ strategies may be materially different from that of the referenced indices.

L&S’ current disclosure statement as set forth in ADV 2 of Form ADV as well as our Privacy Notice is available for your review upon request.