January 9, 2019

…in this world nothing can be said to be certain, except death and taxes —Ben Franklin

There are actually three certainties: death, taxes, and change — L&S Advisors, Inc.

Good riddance. Sorry to be so brutally honest, but good riddance to 2018. It is hard to find investors who are looking back on last year longing for more. To be fair, there was some writing on the wall, but it is only in perfect hindsight that we realize what messages should have been given more credence. Market prognosticators were uniformly bullish last year. Surprise! This year many investment prognosticators are significantly less sanguine, but the uniformity of bullishness should have been an omen that, in perfect hindsight, deserved greater attention last year.

Another omen that should have been a more important guidepost was Trump’s announcement in March that the United States was applying tariffs on goods imported from China. Having a formal background in economics, this development troubled me greatly. Perhaps I slept through the discussion that reviewed the more positive aspects of trade tariffs.

Markets were quick to accept the more classical explanation that tariffs were not good for the U.S. or China or for anyone else. There were, however, discussions that tried to portray this potential policy mistake as a trade “skirmish” or “battle” but not a full-fledged trade war. Semantics might help us feel better, but a trade war is still a trade war, and the market dove and soared based on perceived progress on trade negotiations, and posturing by the Chinese or tweets from the President.

Chinese growth clearly slowed in 2018, and recent data suggest that slow-down continues, and perhaps that was destined to happen regardless. The most recent report shows Chinese growth as weak as it has been since the bottom of the Great Recession. It is impossible to know how much of the Chinese slowdown was due to the trade “skirmish,” but it seems coincidental that Chinese growth slowed as the months of the trade “battle” waged on. Believing in coincidence is not one of my strong suits. China is the second largest economy in the world, and one of the fastest growing, and a slowing China is likely to have global repercussions.

Investors have been hoping that the recently announced 90 day truce (sure sounds like a war, but at least they did not call it a cease fire…) would lead to meaningful progress, and the trade “dispute” would fizzle out. Being the consummate cynic, I can’t help but wonder whether China would agree to work with Donald Trump at all? Any concessions the Chinese make would be declared a victory for the punitive tactics endorsed by the President and his Director of Trade and Industrial Policy, Peter Navarro. Is it possible the Chinese will think they will be better off waiting to negotiate with Trump’s successor, rather than hand him a victory that might keep him in power for another term? (I did admit to being cynical.)

China was not the only economy that slowed as 2018 unfolded. The U.K., mired in one of history’s great self-inflicted wounds, suffered as negotiations between the Brits and the rest of Europe ground to a virtual halt. Brexit may have sounded like a good idea at the time, but jobs based in London will go elsewhere when the U.K. leaves the European Union. While the U.K. is not in a recession, the political uncertainty suggests that the risks are clearly to the downside.

Italy, too, slowed, and their latest GDP report showed an economy contracting mildly. The Italians have not been the poster-child for fiscal restraint, and their most recent budget was rejected by the EU because their deficit was too large. An agreement was ultimately reached, but not before the Italian economy started to slow.

Germany also saw its economy slide into negative growth. With Angela Merkel announcing she would not seek reelection, political uncertainty seems to be on the rise in Germany as well.

The news from France has not been good as citizens have taken to the streets. One of our partners was in Paris over the holidays, and found themselves unable to get back to their hotel when the roads and bridges were closed. That is probably not a good way to maximize sales during the all-important Christmas shopping season.

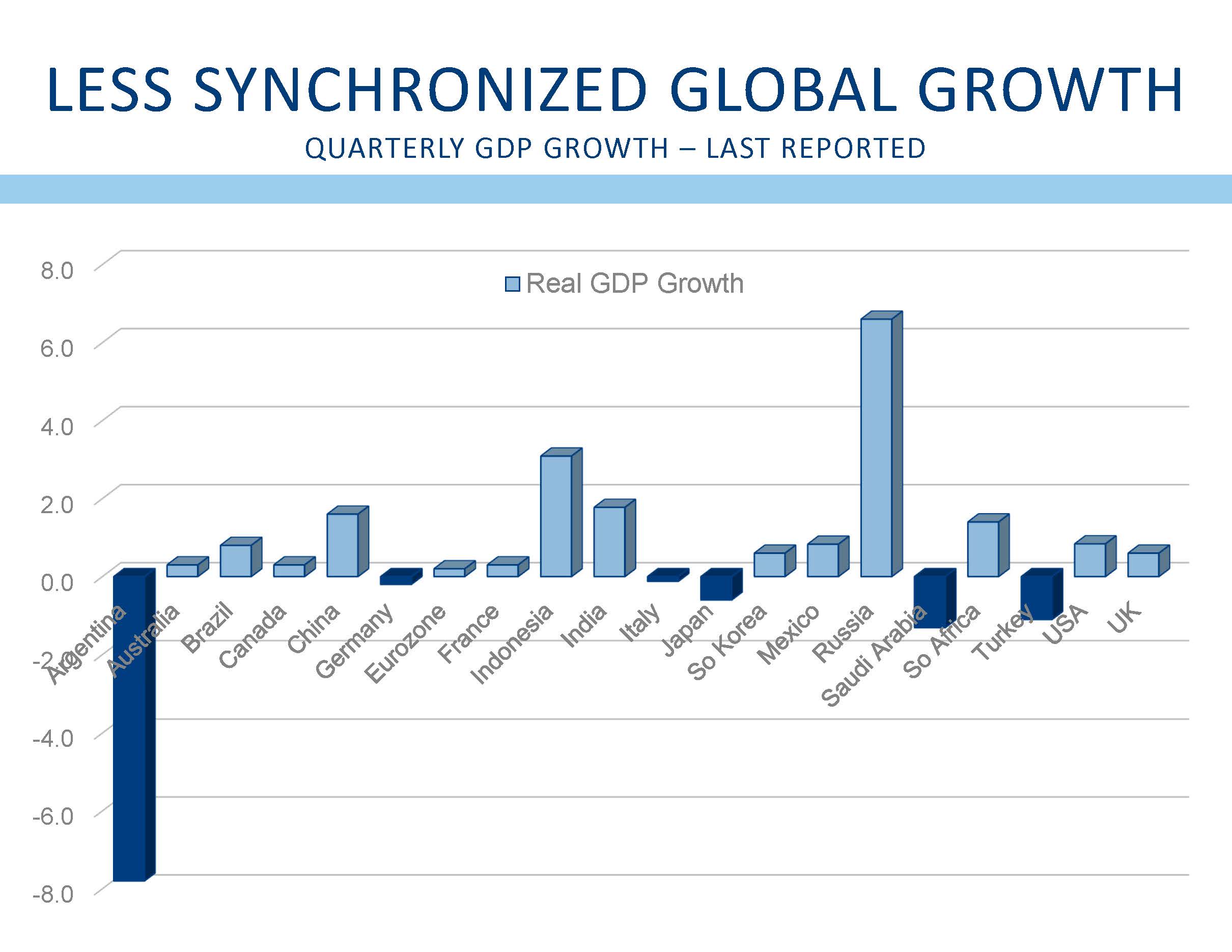

Germany, Italy, Japan, Saudi Arabia, Turkey, and Argentina have all seen their economic growth slide into negative territory. So much for the global synchronized growth so many prognosticators expected as 2018 commenced.

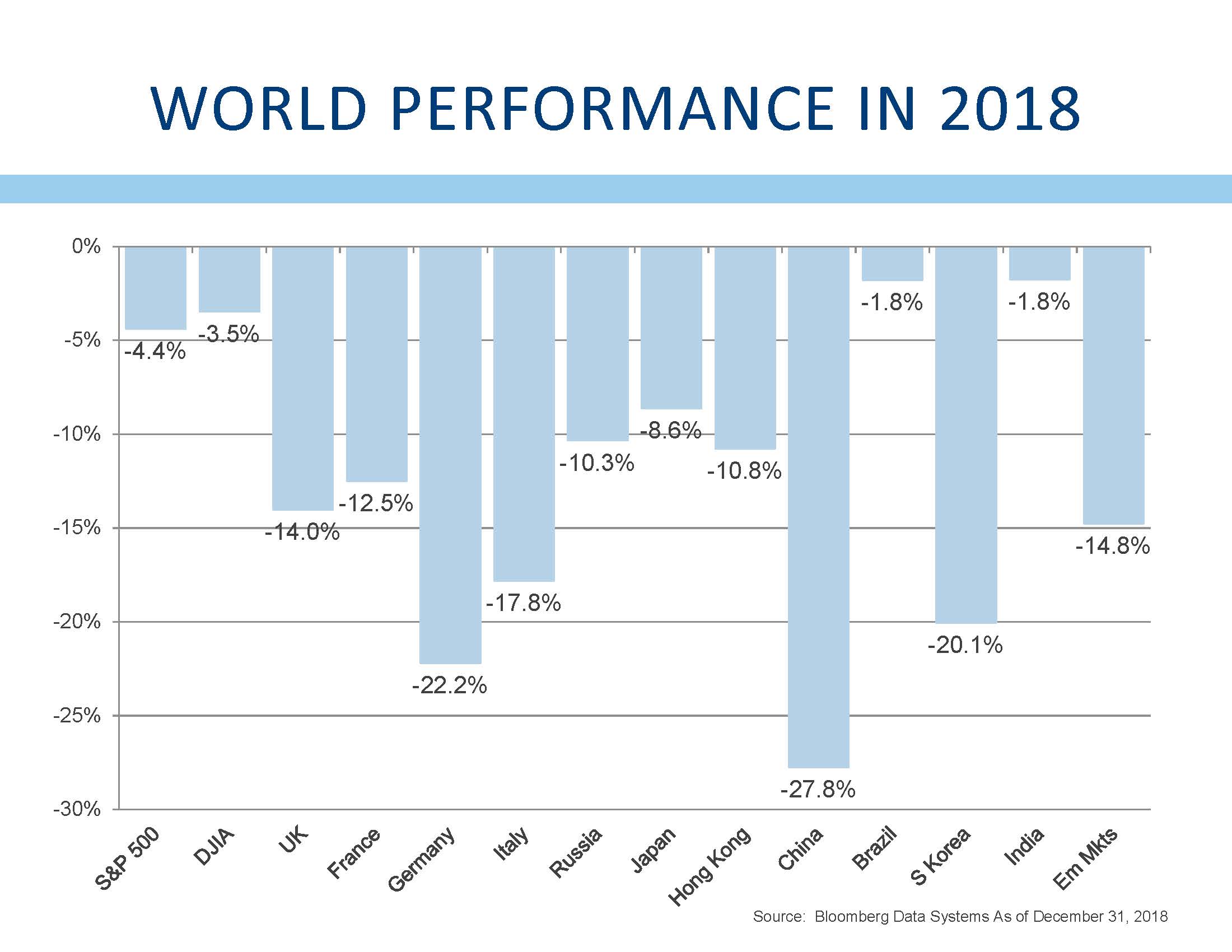

With global growth slowing, it is no wonder that foreign stock markets performed much worse that domestic markets. China, one of the worst performing markets, fell by more than 27% in 2018. Germany was down more than 20%, and many other markets were down more than 10%. The best performing markets were Brazil and India, although both were down for the year. There was simply no place to hide.

Recently, Apple reduced guidance for their expected revenue. Apple does roughly 20% of their sales in China, and about 35% in Asia, and they recently indicated that sales in China had slowed. In particular, CEO Tim Cook said “While we anticipated some challenges in key emerging markets, we did not foresee the magnitude of the economic deceleration, particularly in Greater China….We believe the economic environment in China has been further impacted by rising trade tensions with the United States…” (emphasis is mine)

Apple went on to suggest that earnings would still be at record levels, but record earnings were not sufficient to prevent the stock from falling 10% for the day, and more than 39% since the October highs.

To be sure, cynicism runs deep in the investment world. Why would a stock predicting record earnings be down on the day? Liz Ann Sonders, the investment Strategist for Charles Schwab said “when it comes to the relationship between economic fundamentals and stock prices, better or worse matters more than good or bad.” Apple’s outlook, while still quite good, was worse than expected, and worse trumps good. This has been one of the key lessons of 2018. It seems that uncertainty about trade and general political uncertainty is causing consumers and corporate executives to take a step back to see if the economy weakens further. Does this become a self-fulfilling prophecy that growth slows because people are worried that growth is slowing?

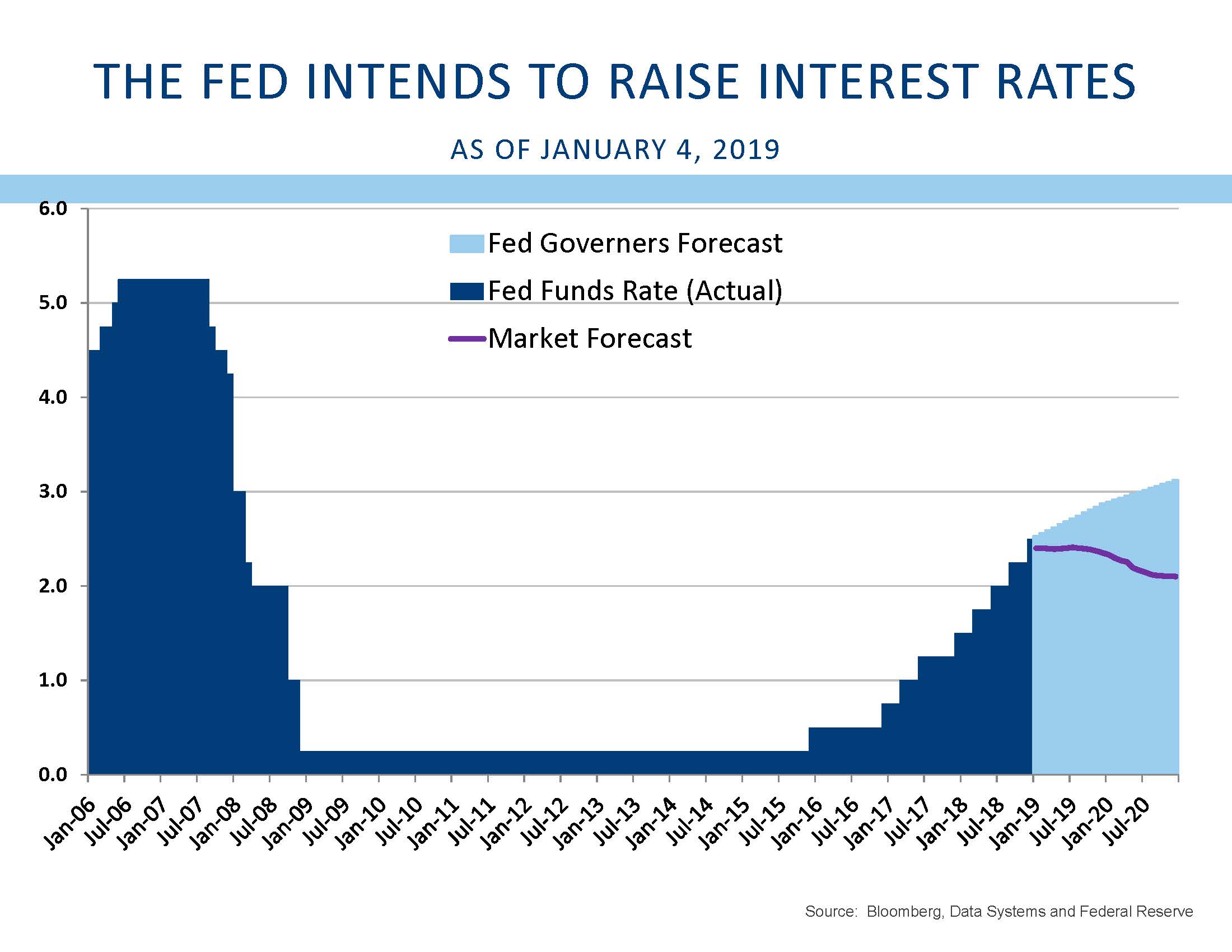

As if the trade “scuffle” was not enough, the policies of the Federal Reserve have been widely criticized as having a negative impact on the market. The Fed increased interest rates in December, its fourth rate hike of the year, and the ninth since rates started higher in December of 2015. Investors had come to the belief that slowing growth overseas would slow growth in the U.S., and that further rate hikes were no longer necessary here at home.

The Fed did modestly lower its forecast for rate hikes in 2019, but the market was disappointed with the tone of the Fed’s comments. The Fed has been working to reduce the quantitative easing it undertook after the Great recession, and Fed Chairman Powell suggested that its balance-sheet reductions would continue unabated. Many market participants believe the Fed is on the cusp of a policy mistake that will push the U.S. into a recession.

The Fed’s position is quite tenable. They are tasked with helping the economy reach full employment and with maintaining price stability. This is widely referred to as their dual mandate. Unemployment is 3.9%, one of the lowest numbers since December, 1969. Job openings exceed the number of available workers, and employers complain about their inability to find competent workers. Part one of the Fed’s dual mandate can only be considered a success.

The news on the inflation front is also quite good with inflation running at about 2%. The recent wage numbers suggest wages are increasing at 3%, and wage inflation has been known to lead the general price level. With unemployment so low, many expect wage inflation to continue to put upward pressure on overall inflation. That is a concern for the Fed, and a reason why they did not back down from their forecast of further interest rate hikes in 2019.

While the Fed is expecting to raise rates twice more in 2019, the market is actually expecting no further rate increases. This disparity will ultimately be resolved, but it is unclear whether the Fed will be forced to reduce the number of rate hikes, or whether the market will have to reevaluate the idea that the Fed is done raising rates for this cycle.

The stock and bond markets are also clearly disagreeing with the Federal Reserve. 10-year U.S. Treasury interest rates have declined from 3.23% in early November to 2.62% as of this writing. Why, if economic growth is so robust, are interest rates falling? Why too are rates lower if inflation is such a concern? Clearly the bond market does not share the Fed’s concern over potential risks.

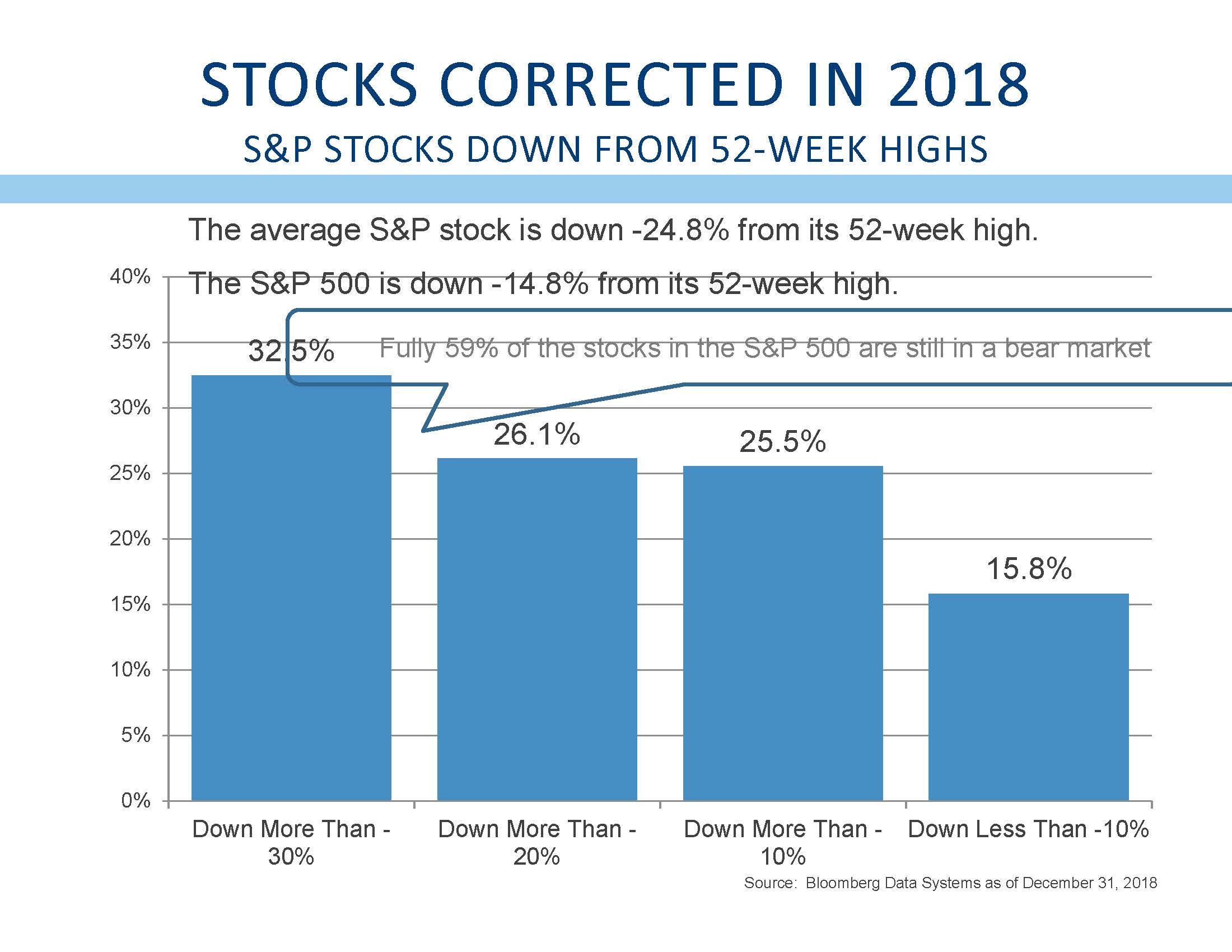

Stocks have also sold off in a violent correction that started in early October. From the late September highs, the S&P has fallen nearly 15%. That number actually camouflages the real carnage felt by investors. As of December 31st, the average stock in the S&P 500 was down nearly 25% from its 52-week high, and 59% of stocks in the index were down more than 20%. This is typically considered a bear market.

Why, if growth is robust, do both stock and bond markets believe the Fed is making a mistake? This is one of the great quandaries for the market. From the Fed’s perspective, the economy is doing well, with growth holding near 3%, unemployment remaining quite low, and inflation just modestly above the Fed’s long-run target. The story from the market is decidedly different. Many investors believe that corporate earnings have or will peak in 2019, and the U.S. will slide into a recession before the end of 2019.

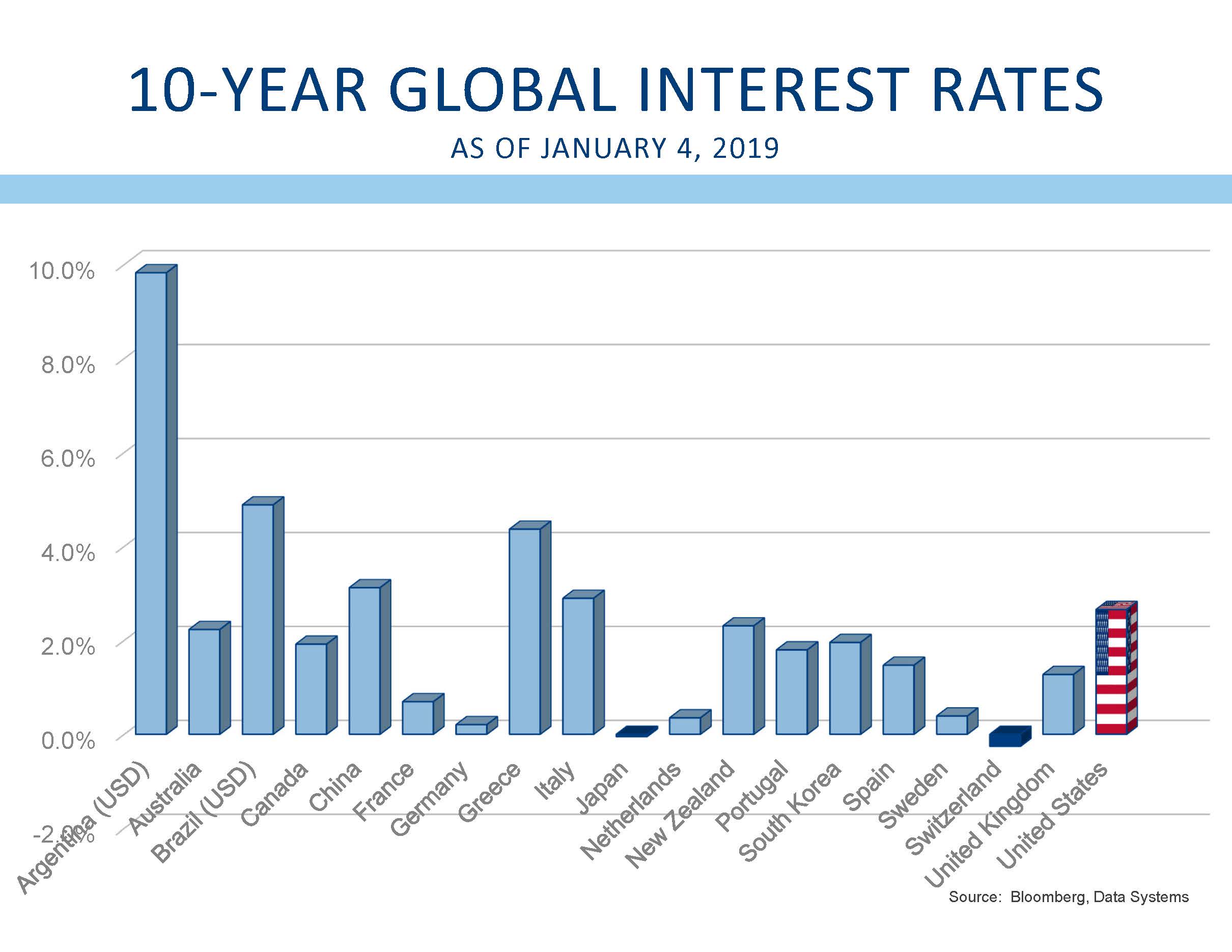

There is a good reason why interest rates can fall without that decline suggesting an imminent recession. Interest rates globally are quite low, and only Brazil, Argentina, Greece, Italy, and China offer interest rates on 10-year bonds that are higher than those available here in the U.S. Why would an investor purchase a German 10-year bond with a yield of 0.15% when US bonds provide nearly 20 times the yield? International fund flows will keep U.S. interest rates low, and low rates may not be indicative of an economy on the cusp of sliding into recession.

Calling the start of the next recession seems key to determining the investment outcomes for the coming year. Stocks generally continue to move up until a recession is imminent. The recent stock market swoon is being seen by some as precisely that warning. Stock prices are discounting earnings declines as investors look ahead into 2019 when economic growth turns down, and takes earnings and stock prices along for the ride.

The case for a recession is not unreasonable. Economic growth has been slowing throughout 2018, and many countries have seen growth turn negative. The trade “dispute” with China continues to put downward pressure on the second-largest economy, and European economies are already struggling. The yield curve has gotten flatter, and an inverted yield curve is one of our best indicators of a coming recession. Commodity prices are down reflecting weak demand. That includes oil, copper, lumber, and other industrial materials. Recent economic reports, including the Purchasing Managers survey (PMI), confirm the economic slowdown. With the political uncertainty of a divided government and the potential for indictments from the Mueller investigation, not to mention the misguided temptation to initiate impeachment proceedings against the President, all suggest rough sledding for the President, and for psychology and market sentiment. With all of that, it is easy to see why markets remain so unsettled.

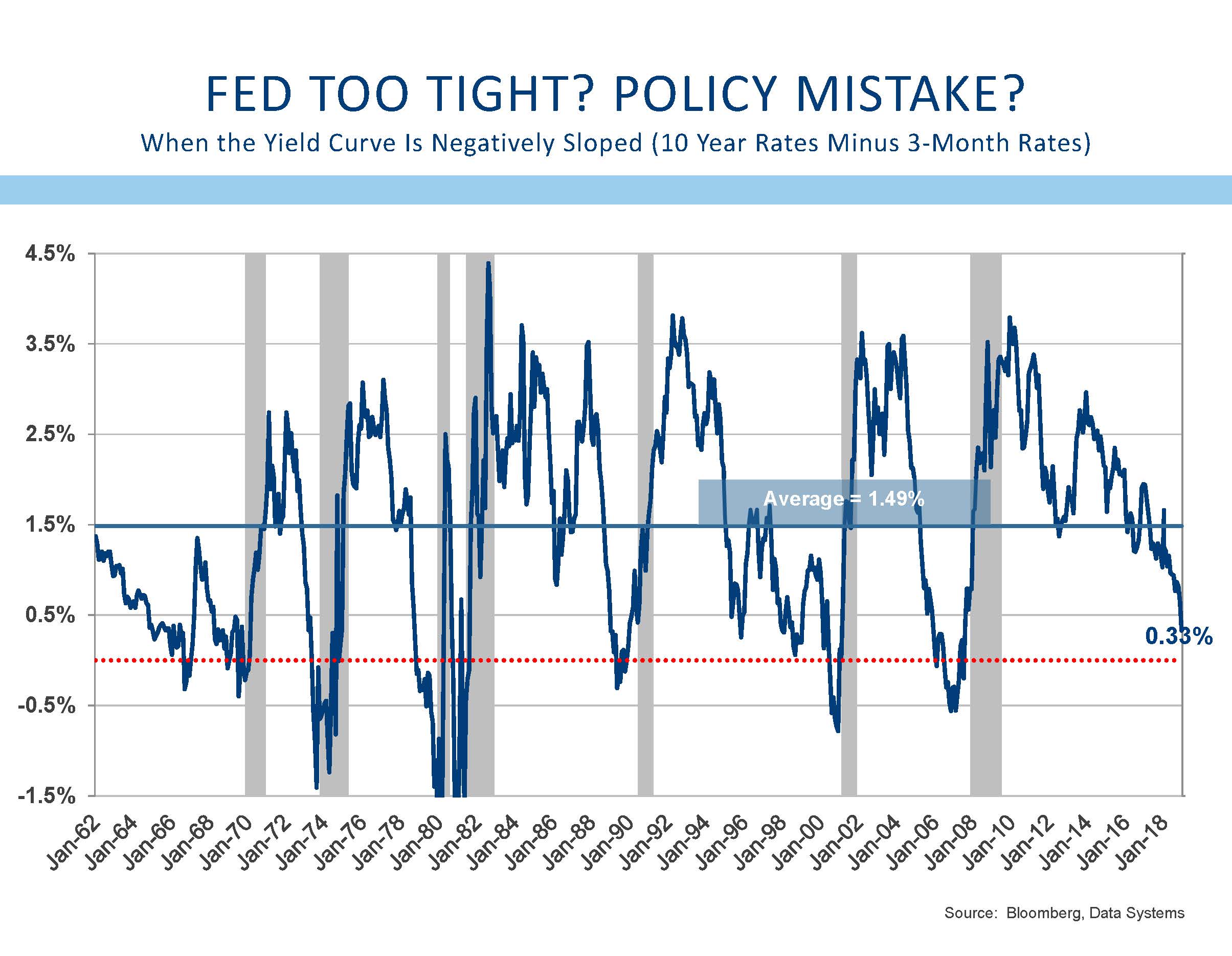

We have repeatedly identified several indicators that have historically provided consistent warning of a pending recession. We mentioned the yield curve which we see as one of the best. When the Fed raises short-term rates too aggressively, markets ultimately realize that rates have moved too high, and longer-maturity bonds yields stop going up. This signal of a policy mistake has an excellent track record of preceding recessions. While the yield curve has not inverted, the spreads are exceedingly narrow, and could be construed as a warning, even if not an outright recession signal.

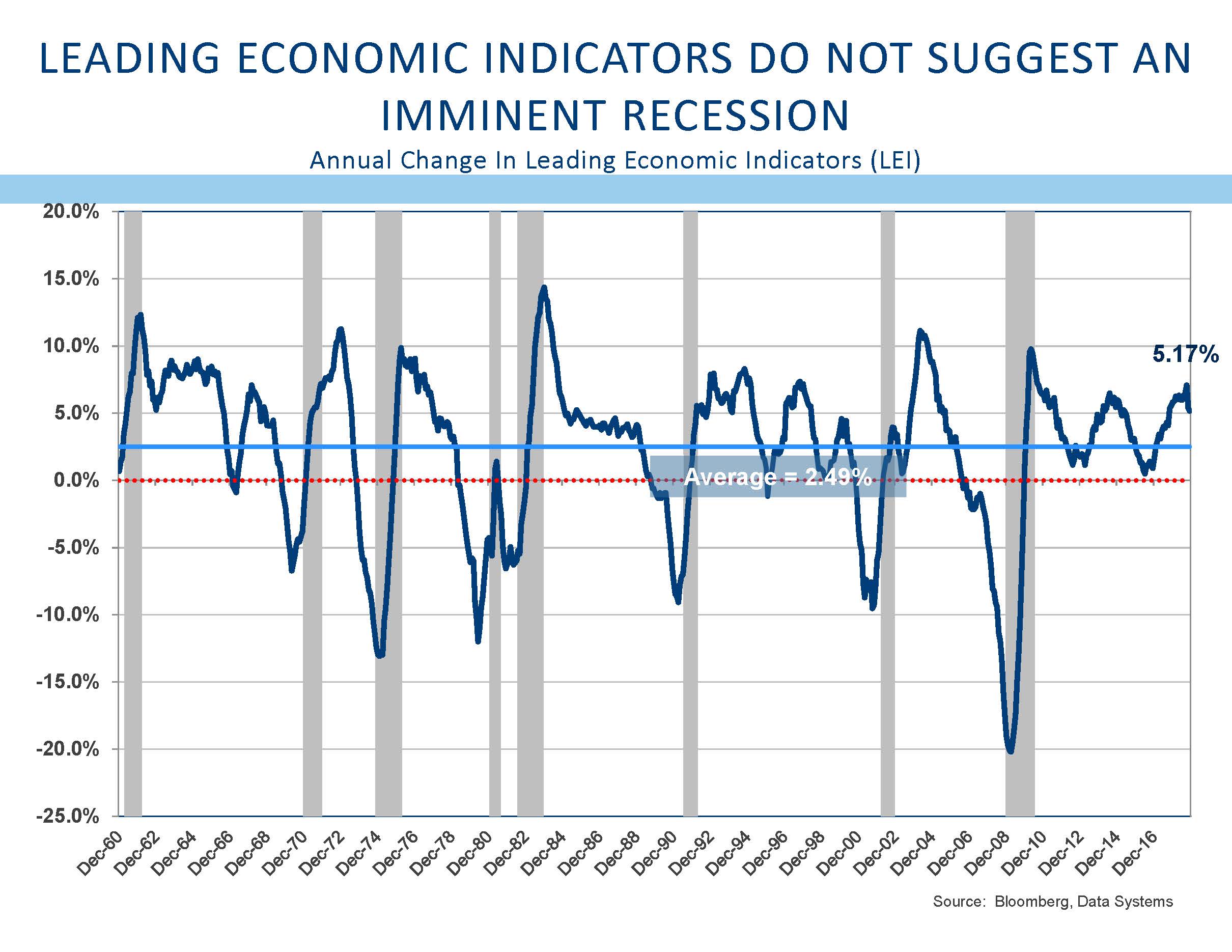

Our second favorite indicator is the Leading Economic Indicators (LEI) published by the Conference Board. When this indicator is down as compared with the level one year prior, it has an excellent track record of predicting a recession. This indicator is currently up 5.2% as compared with last year and does not, at this time, suggest a recession.

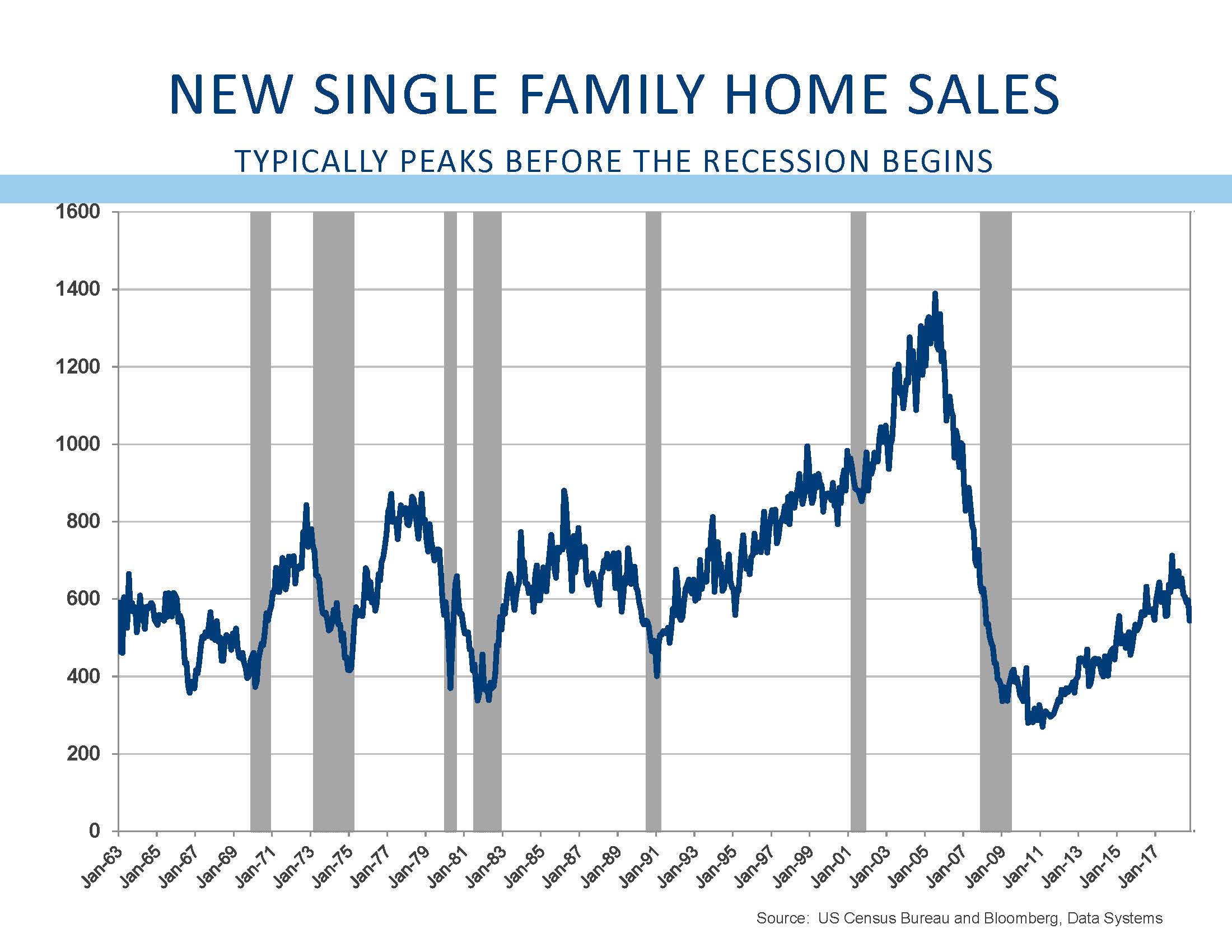

New single family home sales have typically peaked prior to the start of a recession. Here too we must admit that a warning is out there. Sales peaked in March and have fallen by 24% since then. While previous peaks have been many months before the recession, this series is starting to suggest trouble ahead.

When the Fed Funds rate exceeds the rate of inflation or the interest rate on 2-year Treasuries, that has been a sign that Fed policy is too tight. Like the shape of the yield curve, neither of these indicators has given a recession signal, but both are very close to a signal, and deserve further attention. It does not seem prudent to ignore the potential that these indicators will give a recession signal over the next few months.

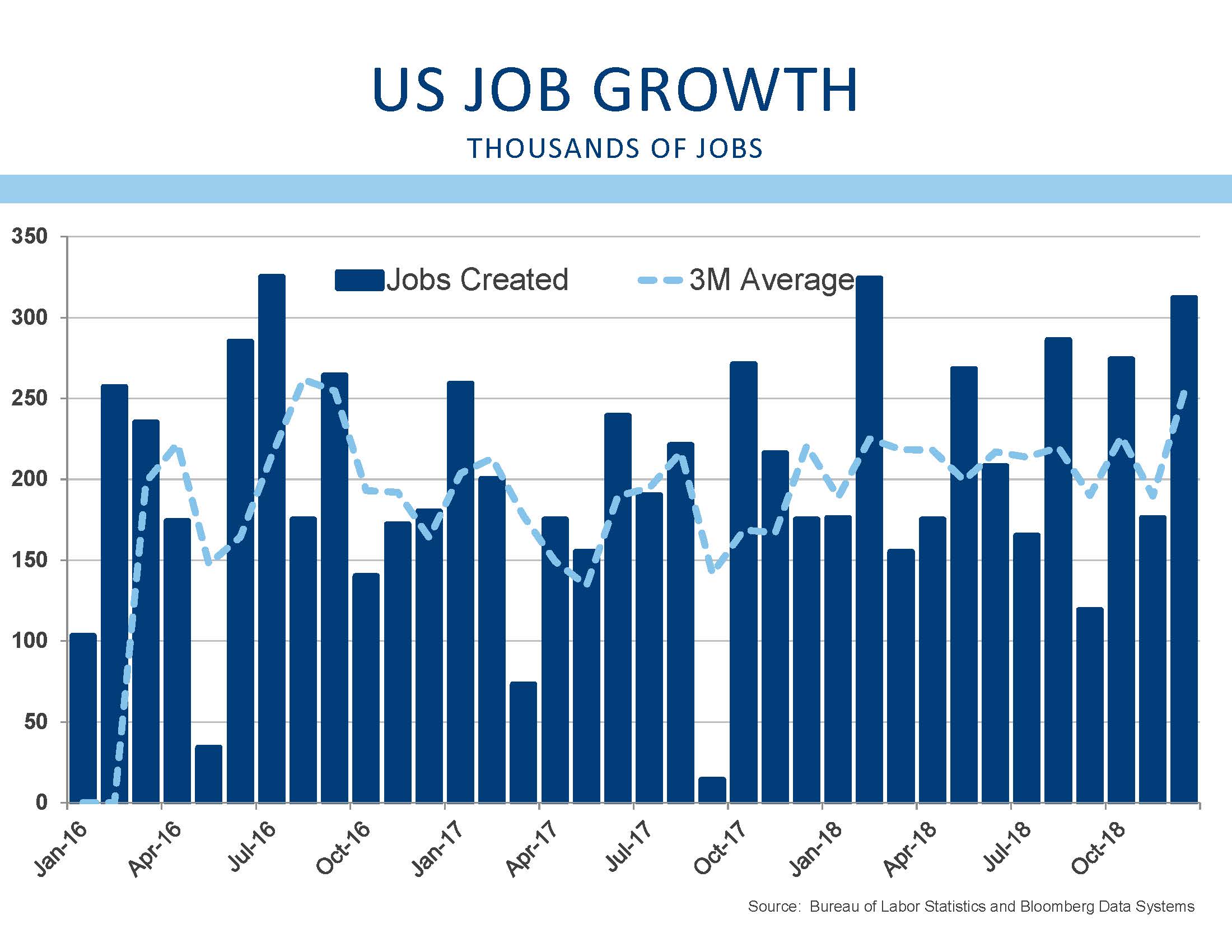

On the other hand, there are ample signs that suggest a recession is not on the immediate horizon. The job report for December showed 312,000 new jobs created. This was much stronger than expected. Previous months were revised upward. While the unemployment rate did increase to 3.9% from 3.7%, the cause of that increase was a significant number of people who rejoined the workforce. This increase in the labor force participation rate reflects the desire for people who had withdrawn from the workforce to return, and this is a very good sign of confidence. It reflects wage growth and the shortage of available workers, and is the best reason for an increase in the unemployment rate.

Other indicators, such as consumer confidence and the percentage of banks that are tightening lending standards, do not convey the risks of an immediate recession.

Further, it is important to remember that recession indicators typically give investors several months or even several quarters of notice prior to a recession. The notion that a we are on the cusp of a recession seems a bit difficult to defend. We recognize that several companies have guided analysts to expect slower growth, but slower growth is not negative growth. Although as the Schwab analyst has said, “better or worse matters more than good or bad.”

Taken together, while the risks of a recession may be higher than they were six or twelve months ago, it is hard to support the notion that the economy will imminently fall into a recession. It is also important to remember that this is not 2008 all over again. Banks are in much stronger financial shape than they were in 2006. While there are some valid concerns about corporate debt levels, those issues are unlikely to create the systemic problems that unfolded in the Great Recession.

Warren Buffet said to “be fearful when others are greedy and greedy when others are fearful.” Stocks are down significantly from the September highs, and at some point it is going to be more fruitful to consider searching for attractive ideas. Down years are not that uncommon, but multiple down years in a row are fairly rare and have only occurred in the midst of severe recessions, and that is simply not the economic environment we are in.

Further, any progress on settling our trade ‘dispute” with China, or additional comments from the Fed that they will consider the data prior to raising interest rates any further would provide markets with a meaningful reason to stop going down. When the market stops considering all news as bad, the potential upside could be substantial.

From all of us at L&S Advisors, we wish you and your family a healthy and happy New Year.

As always, it is important that we know of any changes in your financial situation. Please feel free to call us if you have any questions or comments regarding your investment portfolio.

Bennett Gross CFA, CAIA

President

Disclosure

L&S Advisors, Inc. (“L&S”) is a privately owned corporation headquartered in Los Angeles, CA. L&S was originally founded in 1979 and dissolved in 1996. The two founders, Sy Lippman and Ralph R. Scott, continued managing portfolios together and reformed the corporation in May 2006. The firm registered as an investment adviser with the U.S. Securities and Exchange commission in June 2006. L&S performance results prior to the reformation of the firm were achieved by the portfolio managers at a prior entity and have been linked to the performance history of L&S. The firm is defined as all accounts exclusively managed by L&S from 10/31/2005, as well as accounts managed in conjunction with other, external advisors via the Wells Fargo DMA investment program for the periods 05/02/2014, through the present time.

L&S claims compliance with the Global Investment Performance Standards (GIPS®). L&S has been independently verified by Ashland Partners & Company LLP for the periods October 31, 2005 through December 31, 2015 and ACA Performance Services for the periods January 1, 2016 to December 31, 2017. Upon a request to Sy Lippman at slippman@lsadvisors.com, L&S can provide the L&S Advisors GIPS Annual Disclosure Presentation which provides a GIPS compliant presentation as well as a list of all composite descriptions.

L&S is a registered investment adviser with the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission (“SEC”) and is notice filed in various states. Any reference to or use of the terms “registered investment adviser” or “registered,” does not imply that L&S or any person associated with L&S has achieved a certain level of skill or training. L&S may only transact business or render personalized investment advice in those states and international jurisdictions where we are registered, notice filed, or where we qualify for an exemption or exclusion from registration requirements. Information in this newsletter is provided for informational purposes only and should not be construed as a solicitation to effect, or attempt to effect, either transactions in securities or the rendering of personalized investment advice. Any communications with prospective clients residing in states or international jurisdictions where L&S and its advisory affiliates are not registered or licensed shall be limited so as not to trigger registration or licensing requirements. Opinions expressed herein are subject to change without notice. L&S has exercised reasonable professional care in preparing this information, which has been obtained from sources we believe to be reliable; however, L&S has not independently verified, or attested to, the accuracy or authenticity of the information. L&S shall not be liable to customers or anyone else for the inaccuracy or non-authenticity of the information or for any errors of omission in content regardless of the cause of such inaccuracy, non-authenticity, error, or omission, except to the extent arising from the sole gross negligence of L&S. In no event shall L&S be liable for consequential damages.

The S&P 500 index is a free-float market capitalization weighted index of 500 of the largest U.S. companies. The index is calculated on a total return basis with dividends reinvested and is not available for direct investment. The composition of L&S’ strategies generally differs significantly from the securities that comprise the index due to L&S’ active investment process and other variables. L&S does not, and makes no attempt to, mirror performance of the index in the aggregate, and the volatility of L&S’ strategies may be materially different from that of the referenced indices.

L&S’ current disclosure statement as set forth in ADV 2 of Form ADV as well as our Privacy Notice is available for your review upon request.